Lama Yeshe's Address to the FPMT Family

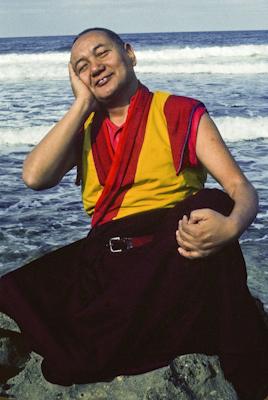

Lama Yeshe, the founder of the FPMT, gave this talk to FPMT center and project directors at the CPMT (Council for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition) meeting at Istituto Lama Tzong Khapa, Italy, January 1983. This was Lama Yeshe's last address to the organization. Edited by Nicholas Ribush.

See also, Bamboo Through Concrete...Growing Tibetan Buddhism in the West, an account by Dr. Nicholas Ribush of his personal experience of Lama Yeshe, based on this talk. For more advice to FPMT centers see Lama Zopa Rinpoche's Online Advice Book.

Why have we established the FPMT? Why are we establishing these facilities all over the world? I think we are clean clear as to our aim—we want to lead all sentient beings to higher education. We are an organization that gives people the chance to receive higher education. We offer people what we have—the combined knowledge of Buddha’s teachings and the modern way of life. Our purpose is to share our experience of this.

We know that people are dissatisfied with worldly life, with the education system and everything else. It is in the nature of our dualistic mind to be dissatisfied. So what we are trying to do is to help people discover their own totality and thus perfect satisfaction.

Now, the way we have evolved is not through you or me having said we want to do these things but through a natural process of development. Our organization has grown naturally, organically. It is not “Lama Yeshe wanted to do it.” I’ve never said that I want centers all over the world. Rather, I came into contact with students who then wanted to do something, who expressed the wish to share their experience with others, and put together groups in various countries to share and grow with others.

Personally, I think that’s fine. We should work for that. We are human beings; Buddhism helps us grow; therefore it is logical that we should work together to facilitate this kind of education. And it is not only we lamas who are working for this. The centers’ resident geshes and the students are working too. Actually, it is you students who are instrumental in creating the facilities for Dharma to exist in the Western world. True. Of course, teachers help, but the most important thing is for the students to be well educated. That is why we exist.

When we started establishing centers there was no overall plan—they just popped up randomly all over the world like mushrooms, because of the evolutionary process I’ve just mentioned and the cooperative conditions. Now that all these centers do exist, we have to facilitate their development in a constructive, clean clear way; otherwise everything will just get confused. We have to develop properly both internally and in accordance with our twentieth century environment. That’s why I’ve already put forward guidelines for how our centers should be—residential country communities, city centers, monasteries and so forth.

The foundation for a center’s existence is the five precepts—no killing, stealing, sexual misconduct, telling lies or intoxicants. We base our other activities—education, administration, accounting, kitchen, housekeeping, grounds and so forth—on those. All this unified energy also depends on the kindness of our benefactors, the devoted people who give us donations. Thus we are responsible to utilize their donations in the wisest possible way, the way that brings maximum benefit to others. For this reason, in a place where hundreds of people are involved, we have to organize—to ensure that we use their energy in the most worthwhile way and not waste their time. Therefore, each of our centers and activities needs a general director—to direct and manage all the human and material resources at our disposal.

What does it mean to be a director? Take, for example, the job of director of one of our country centers. He or she is responsible for everything that happens in the center: education, legal matters, finance, business, community, kitchen and so forth. Computer-like, the directors have to watch everything to make sure that it’s all going in the right direction. And if they see something wrong, it is their responsibility to correct it.

Of course, one person, the director, cannot do everything himself, but under his or her umbrella all center activities function. To control these we need a good management committee and a good place for the committee to meet and discuss things. The director alone should not decide how things should be done. In committee meetings we decide upon projects for the forthcoming year and give various responsibilities to different people. It is then the director’s job to make sure that these people follow the committee’s instructions exactly. If they don’t, the director has the power and authority to correct them. He can even ask people who are disrupting the center’s harmony and proper functioning to leave.

Thus a center director takes incredible responsibility—for the center’s educational success, for its financial success. He has to think like a computer. The directorship is one of the most important aspects of the center. This doesn’t mean that other people do not have responsibility; that’s not true. They are responsible for the areas they have been given; they have their individual responsibilities. And it is not only the people who have been given jobs who have responsibility. Even students who come to a ten-day course, for example, have a certain degree of responsibility. They are working; they are expending energy for Dharma; they are giving—to some extent they do have responsibility. As their hearts are touched they slowly, slowly take on more and more. We can see how we too have evolved in the same way.

Now, the way to bring Dharma to the Western world is to bring the nuclear, the essential aspect of Dharma. Of course, you cannot separate the essence from the Eastern cultural trappings immediately: “This is culture; that isn’t.” However, what you should do is take the practical points of Dharma and shape them according to your own culture. In my opinion, you should be making a new kind of Dharma dependent on each different place and its social customs. Since we are Mahayanists, we have a broad view and don’t mind if Dharma takes different shapes. To bring Dharma to the West we should have a broad view.

Because we have so many centers, I can no longer direct them. Of course, at the beginning I had to direct the centers because the students were always asking, ‘Lama, what to do?’ and we were small enough for me to always be in direct communication with them. But, eventually, we reached a point where I had to ask myself the question, ‘Am I a businessman, a Dharma teacher or what?’ Hundreds of letters were coming in from all over the world; I had to say, “What is this? Should I spend my life answering letters and running centers?” I thought it was wrong for me to spend my life in business because this was not the best way to serve my students. I thought that the most realistic thing to do to benefit them and make my life worthwhile was to go the middle way instead.

So I began to cut down on administrative work. I even wrote to all the centers telling them that they were responsible to make certain decisions; that I could not decide everything and that it is too complicated and far too slow to have all the correspondence coming through Nepal. Therefore, I said we should have a central office as the center’s business point. Of course, I could still be consulted on important matters and could still make decisions on anything. I’m part of the Central Office; I can give my opinion. But it was not necessary to rely on me for everything. That’s why I established the Central Office [now the FPMT International Office, based in Portland, Oregon, USA].

However, to some extent, I am still responsible for whatever happens in our centers. I have not let go of all responsibility, saying, “Let whatever happens happen.” Therefore, I have to know something of what’s going on in the centers: what problems have arisen, how serious they are, what benefits the centers are offering and so forth. The point is that I am not going to let the centers go completely so that they become totally nonsensical, non-beneficial to others and just some kind of ego trip. I don’t believe that should happen. So I don’t want to close myself off. I like to look at and reflect upon what’s happening, but at the same time I don’t want to spend my whole life writing letters. Thus, taking the middle way meant setting up the Central Office, which has reduced my administrative workload and given me more time to spend teaching Dharma. I haven’t done it because I am lazy…well perhaps I am lazy, but at least I have to pretend that I am not!

Quite apart from the fact that I do not have time to do all this administrative work, there are many things to do with running a center that you can do far better than I. You can communicate with people from your own cultural background much better than can a simple Himalayan monk. All the legal and financial work—I can’t do that either. Also, there are many positions to be filled in a center; the right people have to be selected for the right job. You students should do these things yourselves.

So, because all this administrative work was taking me so long, I passed many things on to the Central Office. There is a huge amount of this kind of work to do, that’s why the Central Office is important. It facilitates communication both between the centers and me and among the centers themselves. You see, we do have the human tendency to shut off from each other: “I don’t want you looking at me; I can see my own point of view, I don’t want to share it with you.” Each center has its own egocentric orientation: “We’re good enough; we don’t need to take the best of other cultures.” This is wrong. We have reached our present state of existence through a process of evolution. Some older centers have had good experiences and have learned how to do things well. Doing things well is not simply an intellectual exercise but something that comes from acting every day and learning how to do things until you can do them automatically. Thus it is good that the Central Office has a pool of collective experience so that all our centers can share in it and help reinforce each other.

We have to be able to focus and integrate our energy and store information in a clean clear way so that it can be readily accessed. We should make a structure so that we all know what information is there and how to get it. Without a proper structure, we’d go bananas! Even a couple living together needs to be organized so that their house is clean, there is the food they need and so on. In the centers, we are involved in hundreds of people’s lives; for some reason Dharma has brought all these people together. We are responsible to ensure that we do not waste people’s energy; therefore we have to get ourselves together. This is why organization is very important.

Let’s say, for example, that one of the older students and I have started a center. We are impermanent; we are going to die. What happens when we are dead? We established the center; it has never been organized properly; should it die too? No, of course not. Even though our very bones have disappeared, the center should continue to function. But for people to be able to carry on in its work there should be clean clear directions as to what it was established for. If things are set up right, religious philosophies can carry on for generations and generations. We know this to be an historical fact.

If you think about it, from the point of view of culture, Buddhism is completely culture oriented; it is a complete culture, or way of life, from birth to death. Therefore we are dealing with a very serious thing; we are giving people something that they should take very seriously in their lives. It is not just a one-week or one-month trip. We are offering something that utilizes Buddha’s method and wisdom in the achievement of everlasting satisfaction. That everlasting peace and happiness is what we are working for.

So we have a very important job; it is not just one person’s thing. For that reason I have to say openly to all our center directors that they should not feel they are working for Lama Yeshe—that’s too small. I am just a simple monk; you are working for me? One atom? No—you are working for something much bigger than just one man. You are working for all mother sentient beings. That is important. You should think, “Even if I die, I am doing all of these things for the sake and benefit of all other mother sentient beings.” That is why it is so important to us to have a clean clear structure and direction.

For me, this is very important. I don’t believe I am the principal worker and doing everything. No. I believe what Lama Je Tsongkhapa says in his lamrim: All your success comes from other sentient beings. Thus, other sentient beings are capable of continuing our work, and what will enable them to do so will be having a clean clear direction—not a temporary, Mickey Mouse direction, but a clean clear one. Our aim then is to have a perfectly delineated structure so that even when we are all dead, still, as we wished, our Dharma centers will be able to carry on their work. I believe that human beings are very special. They are intelligent. If we write an intelligent constitution, record an intelligent system of direction, other human beings will be able to keep it going. That is why we have to have a structure.

Now, as far as our structure is concerned, it is simple and natural; a structure that could have been thought out by primitive people, not sophisticated twentieth century ones. I am not sophisticated; I have never been educated in organizational structure or learned about it. I am very simple. Our thing has grown naturally. Because we have been giving continuous teachings, the number of students has grown. Then, from Nepal, those interested students have returned to their homes all over the world and started centers in various places. Some of those have become directors and given different job responsibilities to others interested in helping them.

How is the Central Office constituted? Each of our centers is a part of the foundation of the main office; the office manifests from that base. Do you see the evolution? We give teachings; all the original directors manifest from there; from the directors, energy for new centers builds up; more and more new centers come. Like that, there has been a logical evolution, development from an existing foundation. The directors have built up the entity of the foundation and the Central Office, we communicate, and this is the way the structure develops. To my mind, it is not a sophisticated, egotistical structure but one that has occurred and grown naturally. Now all these directors—administrative, spiritual, business—are the principal nuclear resource, and they make up the Central Office; they are the directorate. They meet; they put forward ideas. But who keeps the Central Office going? These twenty or more people remain in the one location, meeting and working together all the time, all their lives. They have to go back to their own places; they have their own business to attend to. So who does all these things? The director of the Central Office.

Say that a CPMT meeting has decided that all centers should undertake a certain project because of its obvious benefit to the centers, the FPMT, or whatever. It is then the Central Office’s responsibility to ensure that all the centers have all the information and everything else they need to carry out the project. On the other hand, some good idea may not be practical. If I have to go to each center to explain why something should not be done it’s an incredible hassle. I can save time, life and energy simply by telling the Central Office my ideas, which can then be circulated to all the relevant places. This is simple and useful, and it’s the Central Office director’s job to see that all this gets done. We need a clean clear system with which everybody is comfortable.

Therefore when you, the FPMT directors, come to a final decision that is solid, to be implemented, or actualized, in our centers, the Central Office has the authority to make sure it happens. The Office Director cannot direct a center to do something that was not generally agreed, “Because I say so.” “I say so” is not authority enough. The thing is, we get an idea, a meeting of the FPMT directors (CPMT) agrees, and the Central Office ensures that it can be and is implemented. I think that this is the correct way to go about things.

Anyway our aim is clear; it is to educate people. Each center should have strong emphasis on education. The education system and program are essential for us to be successful. Why are we building communities? Because we have no home? No! We are not refugees; we have not started centers to house refugees. Thus it is important for each center to have a strong educational program and a spiritual director to conduct it. This is an essential part of our structure and must be there.

But I am not going to keep telling you things that you know already. Still, it is important that I clarify the reason for our existence and what we are doing. It is important work; we are not joking. We are real. Also, we are confident. I have great confidence in my involvement with Western people; I believe in it. I think that there are things that we can understand in common. We understand each other; therefore we can work together.

Also, it is important for directors to have a great vision; they should not neglect their center’s growth. They should have a very broad view in order to be open to people. In many of our centers we find that already the facilities are too small. Of course, to build adequate facilities takes time and energy; but we should have a broad open view: “We would like to have things this way, without limitations….” Having a broad view is not forcing any issue but simply saying that if we have the opportunity to do various things, we’ll do them. You never know when somebody might come up to you and say, “I’d like to do something beneficial with my money.” At that time you can reply, “Well we have this project ready to develop,” and show that person your plans. If, however, you feel suffocated with what you already have and don’t have any vision of how to expand, you can’t show potential benefactors anything. Therefore you should plan ahead with great vision and have everything ready to show people how you want to expand and improve your facilities.

For example, we have always said that our centers should be living communities. But through experience we have discovered that we cannot yet be self-sufficient. To be a self-sufficient community in the Western sense requires an immense input of energy. Let’s say that the twenty of us here are a community. Can you imagine what we need in order to live according to this society’s standards? We have to live in reasonable comfort. That means we have to have cars, a certain amount of regular income for living expenses and so forth. So how do we do it? From the realistic point of view, it is an incredible job to make each center into a self-sufficient community. You know how much energy you have to take from the outside world.

My observation is that our centers are not run really professionally as self-sufficient communities. Even though we call ourselves communities, from the Western standard of living point of view, other communities are much more comfortable than our Buddhist ones. One of the problems that we are beginning to experience is that of overcrowding. This is not right—we must create the right conditions for people who live in or visit our centers, be they monks or nuns, single laypeople or parents and their children. We are in trouble because we are not doing things according to the Western way of life. Therefore we should take a look at where we are and where we should go from here.

Community life should be normal. Parents and children should be accommodated in our centers so that they can live as normally as possible. Our experience is that they are not; we should learn from that. Of course, our students have big hearts and try their best. It is all a part of our evolution, not something that we have done wrong. But now we have reached a certain point and learned something. Our Dharma family has grown and we need to improve the living conditions at our centers to accommodate everybody. There should be a section where families can live normal family lives; there should be part of the center where strict retreat-type courses can be conducted; there should be monastic conditions for the monks and nuns. Everybody should be normal and comfortable in his or her way of life and everybody should have something constructive to do.

So, not only do we need a clear structure for our international organization; there should be one within each center too. As I said before, each center needs a director and a management committee. The committee consists of heads of the important sections of the center: the resident geshe, the spiritual program director, the business manager etc. and, of course, the director. Thus the committee is not elected, but made up of those who hold responsible positions in the center. These people meet regularly and discuss how things should be done on a day-to-day basis. When they have agreed, they call the residents together and inform them of what they have decided. If the residents agree, well and good, but the committee does have to check with them. Thus all the center’s members are consulted and have a say in decisions that affect them.

In general, this is the way we do it, but sometimes it might be hard for everyone to understand which way a director is going. If they don’t understand, perhaps he can just let go. But most of the time this is the way we work: there is a committee, it makes decisions, we see how the residents feel about them, and if they don’t like the decisions, we can change them. If they agree, then whatever it is, it can be done. In this case, it is the director’s responsibility to see that it happens; he has to make sure that the committee’s decisions are implemented, in much the same way that the Central Office director has to see that the CPMT’s decisions are carried out.

However, with respect to major decisions within a center, even the director and committee cannot decide alone. For example, say all the center’s buildings should be torn down and rebuilt. I don’t think they should make a decision of that magnitude without consulting the other FPMT directors. It is too risky to have just a few people deciding whether or not to demolish an entire center. Similarly, say a center receives a donation of a million dollars. We should definitely call a meeting of all the other directors to decide on how that money should be spent. The director and the committee alone cannot make their own immediate decision, even though they know the local situation much better than all the other directors. The director of that center should put forward his proposals for the others to comment on.

In the same way, there is a limit to the decisions that the Central Office director can make. Above a certain level the other directors should be consulted. Then the Central Office makes sure that what has been agreed to gets done. Also, the Central Office helps me get information about the centers and passes my messages through to the centers. My mail comes through the Central Office, too. The Office is a tool that helps me implement ideas I might have for ways to improve the centers. In this way and the ways already mentioned, the centers benefit from the Central Office. Thus it is important for them to support the Office through annual contributions.

Because we are doing constructive things with long-term plans, we should not expect to be able to judge the benefits of the contributions made to the Central Office on any short-term effects: “This year we gave x dollars to the Central Office but received only y amount of benefit.” The benefit you receive may not necessarily become apparent in this material life. We are planting seeds and it takes time for them to grow. Therefore, as long as you can understand why your center puts money into the Central Office, you can analyze what is going on in the present situation and what are the short- and long-term benefits for the entire FPMT mandala, and check all that against the needs of our growing organization. Only then can you judge whether or not your contribution has been worthwhile. Remember—to bring Dharma to the West we have to have a broad view.