Seeking the "I"

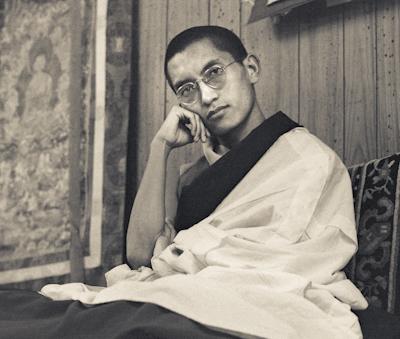

From teachings by Lama Zopa Rinpoche at Lawudo Monastery, Solu Khumbu, Nepal and Instituto Lama Tzong Khapa, Pomaia, Italy, 1977.

Compiled and edited by Kathleen McDonald. First published in Wisdom Energy 2, Publications for Wisdom Culture, Ulverston, England, 1979.

All the problems we encounter in samsara: the cycle of repeated death and rebirth, have their source in the ignorance that grasps at things as though they were self-existent. Our situation in this cycle is similar to being trapped in a large building with many rooms and doors, but with only one door leading out. We wander hopelessly from one part of the building to another, looking for the right door. The door that leads us out of samsara is the wisdom that realizes the emptiness of self-existence. This wisdom is the direct remedy for the ignorance which is both cause and effect of clinging to self, and which believes the self or “I” to be inherently and independently existent. In other words, the I appears to be something it is not: a concrete, unchanging entity, existing in its own right, and our ignorant mind clings to this mistaken view. We then become addicted to this phantom I and treasure it as if it were a most precious possession. Wisdom recognizes that such an autonomously existing I is totally non-existent and thus, by wisdom, ignorance is destroyed. It is said in the Buddhist scriptures that to realize the correct view of emptiness, even for a moment, shakes the foundations of samsara, just as an earthquake shakes the foundations of a building.

Each of us has this instinctive conviction of a concrete, independently existing I. When we wake up in the morning we think, “I have to make breakfast,” or “I have to go to work.” Thence arises the powerful intuition of an I which exists in its own right, and we cling to this mistaken belief. If someone says, “You’re stupid,” or “You’re intelligent,” this I leaps forth from the depths of our mind, burning with anger or swollen with pride. This strong sense of self has been with us from birth—we did not learn it from our parents or teachers. It appears most vividly in times of strong emotion: when we are mistreated, abused or under the influence of attachment or pride. If we experience an earthquake or if our car or ‘plane nearly crashes, a terrified I invades us, making us oblivious to everything else. A strong sense of I also arises whenever our name is called. But this apparently solid, autonomous I is not authentic. It does not exist at all.

This does not mean that we do not exist, for there is a valid, conventionally existent I. This is the self that experiences happiness and suffering, that works, studies, eats, sleeps, meditates and becomes enlightened. This I does exist, but the other I is a mere hallucination. In our ignorance, however, we confuse the false I with the conventional I and are unable to tell them apart.

This brings us to a problem that often arises in meditation on emptiness. Some meditators think, “My body is not the I, my mind is not the I, therefore I don’t exist,” or “Since I cannot find my I, I must be getting close to the realization of emptiness.” Meditation which leads to such conclusions is incorrect, because it disregards the conventional self. The meditator fails to recognize and properly identify the false I that is to be repudiated and instead repudiates the conventional or relative I that does exist. If this error is not corrected it could develop into the nihilistic view that nothing exists at all, and could lead to further confusion and suffering rather than to liberation.

What is the difference, then, between the false I and the conventional I? The false I is merely a mistaken idea we have about the self: namely, that it is something concrete, independent and existing in its own right. The I which does exist is dependent: it arises in dependence on body and mind, the components of our being. This body-mind combination is the basis to which conceptual thinking ascribes a name. In the case of a candle, the wax and wick are the basis to which the name “candle” is ascribed. Thus a candle is dependent upon its components and its name. There is no candle apart from these. In the same way, there is no I independent of body, mind and name.

Whenever the sense of I arises, as in “I am hungry,” self-grasping ignorance believes this I to be concrete and inherently existent. But if we analyze this I, we shall find that it is made up of the body—specifically our empty stomach—and the mind that identifies itself with the sensation of emptiness. There is no inherently existing hungry I apart from these interdependent elements.

If the I were independent, then it would be able to function autonomously. For example, my I could remain seated here reading while my body goes into town. My I could be happy while my mind is depressed. But this is impossible; therefore the I cannot be independent. When my body is sitting, my I is sitting. When my body goes into town, my I goes into town. When my mind is depressed, my I is depressed. According to our physical activity or our state of mind, we say, “I am working,” “I am eating,” “I am thinking,” “I am happy,” and so on. The I depends on what the body and mind do; it is postulated on that basis alone. There is nothing else. There are no other grounds for such a postulation.

The dependence of the I should be clear from these simple examples. Understanding dependence is the principal means of realizing emptiness, or the non-independent existence of the I. All things are dependent. For example, the term “body” is applied to the body’s components: skin, blood, bones, organs and so on. These parts are dependent on yet smaller parts: cells, atoms and sub-atomic particles.

The mind is also dependent. We imagine it to be something real and self-existent, and react strongly if we hear, “You have a good mind,” or “You’re terribly confused.” Mind is a formless phenomenon that perceives objects, and is clear in nature. On the basis of that function we impute the label “mind.” There is no functioning mind apart from these factors. Mind depends upon its components: momentary thoughts, perceptions and feelings. Just as the I, the body, and the mind depend upon their components and labels, so do all phenomena arise dependently.

These points can best be understood by means of a simple meditation designed to reveal how the I comes into apparent existence. Begin with a breathing meditation to relax and calm the mind. Then, with the alertness of a spy, slowly and carefully become aware of the I. Who or what is thinking, feeling, and meditating? How does it seem to come into existence? How does it appear to you? Is your I a creation of your mind, or is it something existing concretely and independently, in its own right?

Once you have identified the I, try to locate it. Where is it? Is it in your head…in your eyes…in your heart…in your hands…in your stomach…in your feet? Carefully consider each part of your body, including the organs, blood vessels and nerves. Can you find the I? If not, it may be very small and subtle, so consider the cells, the atoms and the parts of the atoms.

After considering the entire body, again ask yourself how your I manifests its apparent existence. Does it still appear to be vivid and concrete? Is your body the I or not?

Perhaps you think that your mind is the I. The mind consists of thoughts which constantly change, in rapid alternation. Which thought is the I? Is it a loving thought…an angry thought…a serious thought…a silly thought? Can you find the I in your mind?

If your I cannot be found in the body or the mind, is there any other place to look for it? Could the I exist somewhere else or in some other manner? Examine every possibility.

Once again examine the way in which the I appears to you. Has there been any change? Do you still believe it to be real and existing in its own right? If such a self-existent I still appears, think, “This is the false I which does not exist. There is no I independent of body and mind.”

Then mentally disintegrate your body. Imagine all the atoms of your body separating and floating apart. Billions and billions of minute particles scatter through space. Imagine that you can actually see this. Disintegrate your mind as well, and let every thought float away.

Now, where are you? Is the self-existent I still there, or can you understand how the I is dependent, merely attributed to the body and the mind?

Sometimes a meditator will have the experience of losing the I altogether. He cannot find the self and feels as if his body has vanished. There is nothing to hold on to. For intelligent beings this experience is one of great joy, like finding a marvelous treasure. Those with little understanding, however, are terrified, or feel that a treasure has just been lost. If this happens, there is no need to fear that the conventional I has disappeared—it is merely a sensation arising from a glimpse of the false I’s unreality.

With practice, this meditation will bring about a gradual dissolution of our rigid concept of the I and of all phenomena. We shall no longer be so heavily influenced by ignorance. Our very perceptions will change and everything will appear in a new and fresh light.

Closely examine the objects, such as forms, that appear to your six consciousnesses, analyzing the way in which they appear to you. Thus the bare mode of the existence of things will arise brilliantly before you.

These lines from The Great Seal of Voidness, a text on mahamudra by the first Panchen Lama, contain the key to all meditation on emptiness. The most important factor in realizing emptiness is correct recognition of what is to be discarded. In the objects appearing to our six consciousnesses there is an existent factor and a non-existent factor. This false, non-existent factor is to be discarded. The realization of emptiness is difficult as long as we do not realize what the objects of the senses lack, ie, what they are empty of. This is the key that unlocks the vast treasure house of emptiness.

But this recognition is difficult to achieve and requires a foundation of skillful practice. According to Lama Tsongkhapa, there are three things to concentrate on in order to prepare our minds for the realization of emptiness: first, dissolution of obstacles and accumulation of merit; second, devotion to the spiritual teacher; and third, study of subjects such as the graduated path to enlightenment and mahamudra. Understanding will come quickly if we follow this advice. Our receptivity to realizations depends primarily on faith in the teacher. Without this, we may try to meditate but find we are unable to concentrate, or we may hear explanations of the Dharma but find that the words have little effect.

This explanation accords with the experience of realized beings. I myself have no experience of meditation. I constantly forget emptiness, but I try to practice a little Dharma sometimes. If you also practice, you can discover for yourselves the validity of this teaching.