Introduction to Tantra

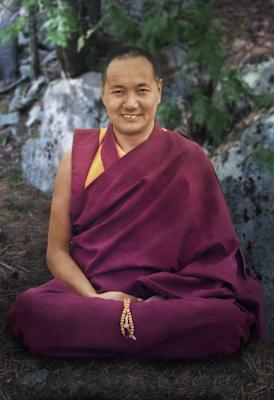

Lama Yeshe gave a commentary to the Avalokiteshvara (Chenrezig) yoga method at Grizzly Lodge, California, in May 1980. This talk is Lama's introduction to this series and constitutes a wonderful explanation of the fundamentals of tantric practice.

These teachings are included in Lama Yeshe's book The Essence of Tibetan Buddhism. You can also watch the videos on our YouTube channel or listen to the audio recordings online.

Introduction to Tantra: First Teaching

Maybe we are going to practice tantric yoga, but it's not easy to do. In order to practice tantric yoga we need a foundation-the preliminaries. First of all, in order to practice tantric yoga, we need to receive an empowerment, or initiation. There are degrees of initiation, but we do need initiation. In order to receive an initiation, we need a certain extent of realization of the three principal paths to enlightenment, which are the wisdom of shunyata, bodhicitta and renunciation. Therefore, it is not easy.

When I say it's not easy, the sense is not that it's a difficult job in terms of money. I mean it's difficult because of our present level. I'm saying it's difficult to practice tantric yoga without a proper foundation, without the right qualifications. Why is it difficult? Because of our level. If we check out our own reality, our present situation, do we have some kind of small understanding of the reality of our own mind? The nature of the mind has two aspects-its relative nature and its absolute nature. Do we know our own mind's relative nature? If we know the relative nature of our own mind, it's easy to direct our mind's attitude. That is each individual's responsibility to check out.

Then, there's bodhicitta. Bodhicitta is a heart that's open to other people rather than totally closed. I'm not talking from the philosophical point of view: "You should be open to other people; if you are closed, I'm going to beat you." I'm not talking that way. If you are not open, the symptoms are great-you suffer a great deal, you're in conflict with yourself and you experience much confusion and dissatisfaction-as you already know; as you already experience every day.

The sense of being open is also not so that others will give you presents, that you'll get chocolate cake. That's not the way, although normally we are like that. Of course, we are not buddha, but to some extent we should have an inner, deep, perhaps intellectual understanding, some discriminating wisdom, that the human need is not simply temporal pleasure. To some extent, we all have temporal pleasure, but what we really need is eternal peace. Having that highest of destinations is the way to be open. It eliminates the problems of everyday life-we don't get upset if someone doesn't give us some small thing. Normally we do. Our problem is expectation. We grasp at such small, unworthy things. That grasping mind is the problem; it produces the symptom of reacting again and again and again. Last year we reacted in a negative way and this year, it's the same or worse. That's how it seems. We're supposed to get better and better but our problems are still overwhelming.

Philosophically, perhaps we can say that karma is overwhelming-consciously and unconsciously. Don't think that karma is just your doing something consciously and then ending up miserable. Karma also functions at the unconscious level. You can do something unconsciously and it can still lead to a big result. Today's problems in the Middle East are a good example. That's karma. They started off small, but those little actions have brought a huge result. As a matter of fact, that's karma.

In order to have the enlightened attitude, an attitude that transcends the self-pitying thought, you need the tremendous energy of renunciation of temporary pleasure-renunciation of samsara. I think you know this already. What do we renounce? Samsara. Therefore, we call it renunciation of samsara. Now I'm sure you're getting scared! Renunciation of samsara is the right attitude. The wrong attitude is that which is opposite to renunciation.

You probably think, "Oh, that's too difficult." It's not difficult. You do have renunciation. How many times do you reject certain situations, unpleasant situations? That's you renouncing. Birds and dogs have renunciation. Children have renunciation-if they want to do something for which they'll get punished, they know how to get around it. That's their way of renunciation. But all that is not renunciation of samsara. Perhaps your heart is broken because of some trouble with a friend so you change your relationship. Anyway, your friend has already given you up so you have to do the same thing and renounce your friend. Neither is that renunciation of samsara.

Perhaps you're having trouble coping with society so you escape into the bush, like an animal. You're renouncing something, but that's not renunciation of samsara.

What, then, is renunciation of samsara? Be careful now-it's not being obsessed with the objects of samsaric existence or with nirvana, either. Perhaps some people will think, "Now that I'm not concerned with pleasure, now that I'm renounced, I would like to have pain." That, too, is not renunciation of samsara. Renouncing the sense pleasures of the desire realm and looking for something else instead, grasping at the pleasures of the form or formless realms, is still the same old samsaric trip.

Say you're practicing meditation, Buddhist philosophy and so forth and somebody tells you, "What you're doing is garbage; nobody in this country understands those things." If somebody puts the nail of criticism into you like that and you react by getting agitated and angry, it means that your trip of Buddhism, meditation or whatever is also samsaric. It has nothing to do with renunciation of samsara. That's a problem, isn't it? You're practicing meditation, Buddhism; you think Buddha is special, but when somebody says, "Buddha is not special," you get shocked. That means you're not free; you're clinging. You have not put your mind into the right atmosphere. There's still something wrong in your mind.

So, renunciation of samsara is not easy. For you, at the moment, it's only words, but the thing is that renunciation of samsara is the mind that deeply renounces, or is deeply detached from, all existent phenomena. You think what I'm talking about is only an idea, but in order for the human mind to be healthy, you should not have the neurotic symptom of grasping at any object whatsoever, be it pleasure or suffering. Then, relaxation will be there; that is relaxation. You don't have superstition pumping you up. We should all have healthy minds by eliminating all objects that obsess the ego. All objects. We are so concrete that even when we come to Buddhism or meditation, they also become concrete. We have to break our concrete preconceptions, and that can only be done by the clean clear mind.

For example, when you see an old tree in the distance and think that it's a human being, your superstitious mind is holding that wood as a human being. In order to eliminate your ego's wrong conception, you have to see that collection of energy as wood. If you see that clean clear, the conception holding that object as a human being will disappear. It's the same thing: the clean clear mind is the solution that eliminates all concrete wrong conceptions.

Because our conceptions are concrete, we are not flexible. Somebody says, "Let's do it this way," but you don't want to change. Only you are right; other people are wrong.

Tied by this kind of grasping at samsaric phenomena at the conception level, it is difficult for you to see the possibility of achieving a higher destination. You are trapped in your present limited situation and can see no way out of it.

Practically, renunciation means being easygoing-not too much sense pleasure and not so much freaking out. Even if you have some pain, there's an acceptance of it. The pain is already there; you can't reject it. The pain is already there, but you're easygoing about it.

Perhaps it's better if I put it this way-you're easygoing with the eight worldly dharmas. I think you already know what they are. If you are easygoing with them, that's good enough. You should not think that renunciation is important simply from the Buddhist philosophical point of view in order to reach liberation. Renunciation is not just an idea; you should understand renunciation correctly.

Shakyamuni himself appeared on this earth. He had a kingdom; he had a mother and a father; he drank milk. Still, he was renounced. There was no problem. For him, drinking milk was not a problem-ideologically, philosophically. But we have a problem.

Another way of saying all this is that practicing Buddhism is not like soup. We should approach Buddhadharma organically, gradually; we are fulfilled gradually. You can't practice Dharma like going to a supermarket, where in one visit you can take everything you want simultaneously. Dharma practice is some-thing personal, unique. You do just what you need to do to put your mind into the right atmosphere. That is important.

Perhaps I can say something like this: Americans practice Dharma without comprehension of the karmic actions of body, speech and mind. American renunciation is to grasp at the highest pleasures; Americans try to become bodhisattvas without renunciation of samsara! Is that possible? Perhaps you can't take any more of this! Still, be careful. I'm saying that there's no bodhisattva without realization of renunciation. Please, excuse my aggression! Well, the world is full of aggression, so some of it has rubbed off on me.

Of course, actually, we are very fortunate. Just trying to practice Dharma is very fortunate. But also, it's good to know how the gradual path to enlightenment is set up in a very personal way. It's not just structured according to the object. If you know this, it becomes very tasty. Of course we can't become bodhisattvas all of a sudden, but if you can get a clean clear overview of the path's gradual progression, you'll approach it without confusion.

Dharma brothers and sisters are often confused because of the Dharma supermarket. There are so many things to choose from. After a while you don't know what's good for you. The first time I went to an American supermarket I was confused; I didn't know what I should buy and what I shouldn't. So, it's similar. You should have clean clear understanding. Then you can act in the right direction with confidence.

So, you should not regard the three principal paths to enlightenment as a philosophical phenomenon. You should feel that they are there according to your own organic need.

If you hunger for sentimental temporal pleasure, it's not so good. You don't have a big mind. Your mind is very narrow. You should know that pleasure is transitory, impermanent, coming and going, coming and going like a Californian friend-going, coming, going! When you have renunciation, you somehow lose your fanatical, over-sensitive expectations. Then you experience less suffering, your attitude is less neurotic, and you have fewer expectations and less frustration.

Basically, frustration is built up by superstition, the samsaric attitude, which is the opposite of renunciation of samsara. Following that, you always end up unbalanced and trapped in misery. We know this. So, you should see it clean clear. That is the purpose of meditation. Meditation is not on the level of the object but on that of the subject-you are the business of your meditation.

The beauty of meditation is that you can understand your own reality, and if you understand your own problems in this way, you can understand all living beings' situation. But if you don't under-stand your own reality, there's no way you can understand others, no matter how hard you try-"I want to understand what's going on with my friend"-you can't. You don't even understand what's going on in your own mind. So, meditation is experimenting to see what's happening in your own mind, to know the nature of your own mind. Then, as Nagarjuna said, if you understand your own mind, you understand the whole thing. You don't need to put effort into trying to understand what's going on with each person individually. You don't need to do that.

We talk about human problems; we talk about our own problems every day of our lives. The reason I have a problem with you is because I want something from you. If I didn't want something from you, I wouldn't have a problem with you. That's why the lamrim teaches that attachment, grasping at your own pleasure, is the source of pain and misery, and being open, concerned for other people's pleasure, is the source of happiness, realization and success. For some reason, it's true; even on the materialistic level. I tell you, actually-forget for a moment about Buddhadharma and the universal sentient beings-even if you simply want good business, somehow, if you have a broad view and want to help other people-your family, your nation-somehow, for some reason, you will be successful. On the other hand, if you are only concerned for "me, me, me, me, me," always crying that "me" is the most important thing, you'll fail, even materially. It's true; even material success will not be possible.

Many people, even in this country, have material problems because they are concerned for only themselves. Even though society offers many good situations, they are still in the preta realm. I think so, isn't it? You are living in America but you're still living in the preta realm-of the three lower realms, the hungry ghost realm; you are still living in the hungry ghost realm.

Psychologically, this is very important. Don't think that I'm just talking about something philosophical: "You should help other people; you should help other people." I'm saying that if you want to be happy, eradicate your attachment; cut your concrete concepts. The way to cut them is not troublesome-just change your attitude; switch your attitude, that's all. It's not really a big deal! It's really skillful, reasonable. The way Buddhism explains this is reasonable. It's not something in which you have to super-believe. I'm not saying you have to try to be a superwoman or superman. It's reasonable and logical. Simply changing your attitude eliminates your concrete concepts.

Remember equilibrium? Equilibrium does not mean that I equalize you externally. If that were so, then you'd have to come to Nepal and eat only rice and dhal. Equilibrium is not to do with the object, it's to do with the subject; it's my business. My two extreme minds-desire, the overestimated view and grabbing, and hatred, the underestimated view and rejecting-conflict, destroying my own peace, happiness and loving kindness. In order to balance those two, I have to actualize equilibrium.

The minute your fanatical view and grasping start, the reaction of hatred has already arrived. They come together. I think you have experienced this; we do have experience. The minute something becomes special for you, breaks your heart, in that minute, the opposite mind of hatred has come. They are inter-dependent phenomena. For some reason, by having an ego, the tendency is always to be unbalanced, extreme. We have so many problems-individual, personal problems; they all come from the extreme mind.

Actually, you should pray not to have desirable objects of the fanatical view. You're better off without them. They are the symptoms of a broken heart and lead to restlessness. You should be reasonable.

You can see that some people's relationships are reasonable. Therefore, they last for a long time. If people's relationships start off extreme, how can they last? You know from the beginning, they cannot last. Balance is so important.

The thing is, why don't we have good meditation? Simply-why don't we have good meditation? Why can't we concentrate, even for a minute? Because our extreme mind explodes; internally, there's a nuclear blow-up. That's all. We're out of control. We should learn how to handle that explosion.

First of all, this problem is not something that has happened by accident. We should know that there's an evolution to its existence. Therefore, our first order of business should be to investigate the extreme view of our ego mind.

Now, I'm going to go quickly. This morning you did the meditation of contemplating on your breath in an easygoing way. But as meditators, we are also extreme. The reason is that samsara is so overwhelming and our reaction is, "I want to meditate; I should meditate." We push and push, pump and pump; we're very unnatural. That's no good. Then our minds freak out. Then we don't like coming to the meditation center; we want to escape to the jungle. We make ourselves like that; we beat our mind. That is unskillful. It's true. I think most meditators are unskillful-like me. Unskillful.

The thing is, saying it another way, we are too intellectual. Even though we don't learn intellectual philosophy, we are still intellectual. Intellectually, we push ourselves this way and that. It's unnatural. We are unnatural. That's the problem. We are so artificial. We're artificial, plastic intellectuals; we're a new type of plastic product-plastic intellectuals!

We should be happy. Approaching Dharma, approaching meditation, we can be happy. It means we want to be happy. We know we all want to be happy, but we often misunderstand lamrim and Dharma. We think that when we come to Buddhism, we should suffer; our lives should be ascetic; we should be mean to ourselves. That should not be the case. You love yourself, you have compassion for yourself, so you should not put in tremendous, tight effort when you meditate. You should not put in tremendous effort! You should learn to let go. Actually, it's true-meditation is easygoing; using simple language, it's easygoing.

So, contemplate your breath without expecting good things to happen or bad things to happen. Anyway, at that time, it's too late to be concerned whether good or bad things are going to happen. Whatever comes comes; whatever doesn't come doesn't come. At that moment, you can't do anything about it. So, contemplate your breath. Now, when you reach the point where maybe there are neither good thoughts nor bad thoughts, just medium, it means you're successful. At that time, according to your level, just let go; let go. Have no expectations of what's happening, what's going to happen, what's really happening-no expectations. Just let go.

When distractions come-perhaps your ego imagines, "Oh, I'm getting pleasure"-don't reject them; contemplate such notions. In that way, you can reach the point where the first notion disappears, which shows that the appearances your ego imagines are false. When they clear, contemplate the resultant clarity. If you are unable to contemplate that clarity, move your mind a little by thinking, "I have just caught my ego muddying my mind with illusions and overestimated conceptions; so many living beings suffer from such conceptions and are unable to catch them as I can," and generate much compassion or bodhicitta. You can also generate the determination to release other sentient beings from that ignorance, while being aware that, "At the moment, I don't have the ability to really lead other sentient beings into clarity, therefore, I need to clear up my own mind more."

Then go back to contemplating your own thought again. Through your own experience, you know that your mind, or thought, or consciousness, has no color or form. Its nature is like a clean clear mirror that reflects any phenomenon. That is your mind, your consciousness, your thought. The essence of thought is perfect clarity. The movement of thought creates conflict, but when you investigate the nature of the subject, you find that the essential character of thought, even bad thought, is still perfect clarity. It is clean clear, like a mirror, and reflects even irritating objects. Therefore, when even bad thoughts come, don't get upset, don't cry, and don't criticize yourself-instead, use the technique of simply being aware; just contemplate the clarity of the subject, your own mind. If you do that, it will again become clear, because clarity is its nature. Similarly, when good thoughts come, instead of getting busily distracted by the object, again contemplate the clarity of the subject, your own mind.

Another way of saying this is that when you have a problem of thinking, "This is a good thought; this is a bad thought," remember that in fact, both types of thought are unified in having clarity as their nature. If I pour two glasses of water into one container and shake it up, the water looks disturbed but the nature of the water from both glasses is still clean clear. Shaking them up together doesn't turn the water into fire; it still retains its clean clear water energy.

Sometimes it looks complicated when we present the three principal paths to enlightenment in the Tibetan way, but actually, they're very simple. When you are contemplating and a thought arises, move from that thought and practice renunciation. When another thought comes, move from that to bodhicitta. Then again go back and contemplate the clarity of your own consciousness. That's easy-you're just moving your mind into renunciation, bodhicitta or shunyata. You're doing well! You're making your life worthwhile.

When we explain the lamrim, we can go into so much detail. You can explain renunciation so extensively that you could spend thirty days talking about renunciation alone; and thirty days on bodhicitta alone; and thirty days on shunyata alone. Maybe we need all that, but when you're practicing, you can put those three together such that just one movement of your mind becomes renunciation; one movement becomes bodhicitta; one movement becomes shunyata. You can do this. Sometimes when we give extensive explanations you think, "Wow; this is too much." But if you put it practically, when you practice, the lamrim can become in some ways small.

Perhaps that's enough for today. However, when you reach the point of clean clear comprehension, just leave your mind on that. Let go and don't intellectualize.

Next chapter: Introduction to Tantra: Second Teaching »