Immeasurable Love and Immeasurable Equanimity

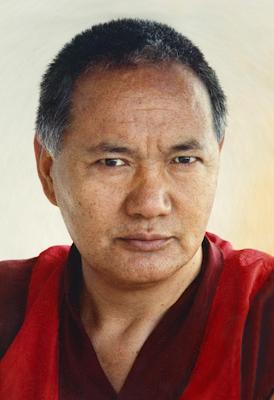

This teaching on the four immeasurables is excerpted from A Commentary on the Yoga Method of Divine Wisdom Manjushri, given by Lama Yeshe at Manjushri Institute, Cumbria, England, in August 1977. Edited by Nicholas Ribush. Published in Mandala magazine, July 2014.

The four immeasurables are immeasurable equanimity, love, compassion and joy. I’ll talk about just a couple of these.

The meaning of immeasurable, or limitless, love is clear from the words themselves. Fundamentally, we all have love; even animals have love. But the problem with our normal human love is that it’s limited. We choose our love objects very selectively, whether they be other people or anything else. There are innumerable phenomena throughout the universe but we choose just a few favorite objects to love. This kind of fanatical love is actually a problem. Normally, we say love is always good. Its positive side can be good, but its extreme, narrow side is not. One reason it’s a problem is that it gives us an extreme view of its object, where we exaggerate its good qualities. Another is that it gives rise to the symptoms of conflict that always arise from the dualistic mind. The inevitable reaction to fickle, narrow love is conflict and discomfort.

Take, for example, the Dharma student. When you first get into Buddhism, your love changes slightly in that it now becomes, “I love Buddhism; I love Dharma; I love Lama.” Then it develops further in this direction: “This is really good. Before, I was down, but Buddhism has brought me right back up. Now I’m happy.” Now you’ve really got a taste for Dharma. The problem is that every time you imprint, “This is good; this is good; this is good; Dharma good; meditation good,” instinctively there arises the mind that thinks that anything that is not Buddhism is unimportant. Especially when you start studying philosophy and learn that there are aspects of other religions’ philosophy that contradict what we believe in Buddhism, you start to put other religions down. You get to the point where you don’t even like to hear the words Christianity, Islam, Hinduism and so forth.

That means you’ve lost your love. Instead of making you more tolerant and free, what you’ve been calling love has become a cause of conflict. I’m talking about love from the religious point of view. When you say, “I love Dharma,” be careful that you don’t love too much.

The point is that you should be using Dharma to solve your own problems, not create more. That’s its only purpose. The function of Dharma is to become an antidote to your own problems. If your love of Dharma causes conflict in your mind, makes you more narrow and limits your communication such that you just want to ignore practitioners of other religions, your love’s your problem.

The way your love becomes limitless is not through blind religious faith. It’s not that someone tells you your objects of love are innumerable and you simply have to believe it. There’s clear logic behind it. Say there’s somebody whom you already love. Ask yourself why you love that person. Usually you’ll reply that it’s because that person’s kind to you. That reason applies equally to all other sentient beings, but you should know all this from having studied the lamrim, so I’m not going to go into any more detail here. This is one of the reasons why understanding of the lamrim is a prerequisite to taking tantric teachings.

But don’t take immeasurable love literally. Just because you love all sentient beings doesn’t mean you have to give people whatever they ask for or sleep with everybody. True, profound, universal love can be wrathful too. True love doesn’t have to come with a smile; it can come with a frown. Our problem is that we interpret love too superficially. If people frown at us, we automatically assume they don’t like us.

One Tibetan yogi said, “Evil friends don’t necessarily look like scorpions.” What he meant was that sometimes the people who are nicest to us are the worst for us. Scorpions are clearly dangerous, and their very appearance makes us afraid. But a person who strokes us lovingly on the arm, gives us gifts and whispers lovingly in our ear can be more dangerous than a scorpion. Such a person might even appear to be kinder to us than Lord Buddha. He was incredibly kind, but he never stroked our arm, gave us gifts or whispered in our ear. The false friend might demonstrate such superficial loving actions, but in the end will cheat us and ruin not only this life but also many lives to come.

We often find problems between parents and children. Most parents instinctively love their children, no matter what the children do. But when the children fail or do stupid things, the parents get worried. Sometimes their emotions and frustration manifest unskillfully as anger and aggression and the children think that their parents really hate them. They don’t see the deep love behind the scolding. This is just another example where what’s on the surface belies what’s underneath.

I don’t need to say anything about immeasurable compassion and joy, but I will make a couple of points about immeasurable equanimity. This way of equalizing all sentient beings is not the same as the communist ideal. It’s completely different. But it looks as if the communists incorporated some of Lord Buddha’s ideas into their politics, or perhaps it would be more accurate to say they dragged them through the mud. But taking profound philosophies into dirty, mundane, idealistic politics isn’t going to work. You can’t make everybody equal by force. Equality has to manifest from your consciousness. Equanimity is a state of mind, not an equal distribution of material possessions.

We should not be confused about this. Young people in the West these days are very idealistic. They get very excited when they hear that everybody should be equal. They feel that the West is too affluent and get quite emotional about the rich in particular. They’re uncomfortable to start with, so the potential for explosion is there. Then when they hear this kind of philosophy, everybody should be equal, anger and jealousy erupt. They get angry at society, the government, the wealthy and almost everybody else. The idea of equality itself is good, but the question is, how to put it into action realistically? To do that, you need a lot of wisdom. It’s difficult to put into action. The Chinese say they’re communists but their society has many, many different classes and standards of living.

Therefore, don’t be confused and go rushing about telling everybody that you heard this fantastic idea that all beings should be equal and start campaigning to make it happen. They’ll lock you up. I’m not talking politics. Don’t take profound spiritual truths that have to do with inner, mental development and interpret them on the physical level.

If you develop equanimity toward all sentient beings, you release all mental agitation. If you are extremely neurotic, if your consciousness is not fundamentally even, you’ll find it impossible to direct your mind into single-pointed concentration. If you can’t do that, it’s very difficult to practice tantric yoga.

The extreme mind is a big problem. Lord Buddha had two brothers. One of them had unbelievable lust. He was always running after women. He was totally impossible. He was so overwhelmed with lustful hallucinations that there was no way that Lord Buddha could give him teachings. For example, say I’m in a nightclub with twenty girls, dancing and drinking, and you come up to me, “Hey, let me tell you some Dharma.” I’m going to go berserk. Even if Lord Buddha himself wanted to give me teachings I’d tell him to leave me alone. It was like that. So he had to come up with another solution.

One day Lord Buddha showed this brother a vision of another realm. It was a hellish environment with flames and smoke all around, and in the middle there was a huge cauldron sitting on a big fire, bubbling with boiling oil and surrounded by fearsome protectors. Somebody asked what the cauldron was for and Lord Buddha’s brother heard one of the protectors say, “Shakyamuni’s brother is up there on earth, dancing, drinking and lusting his life away, but when he dies he’s going to be reborn right here in this pot.” He totally freaked out. Suddenly he comprehended what he’d been doing and what was going to result. He was so upset that he couldn’t even eat. Then with his great skill, Lord Buddha manifested a vision of a beautiful, peaceful environment that was in complete equilibrium. No extreme suffering; no extreme happiness. That made his brother’s mind very tranquil and even, and at that moment, Lord Buddha gave him teachings. As a result, he realized the emptiness of his own mind, released his ego and became an arhat.

Therefore, to practice the [Manjushri] yoga method, you need a firm foundation of equanimity so that you can control your mind and set it in the one direction. I can’t stress enough how necessary this is. But if you can develop equanimity, you will find that state of mind itself extremely blissful. The dualistic mind is a mind of extremes—uneven and unbalanced. It’s a painful mind. It’s the psychological equivalent of constantly having a nail poked into you. The extreme mind is a complete hindrance to your developing the peaceful, blissful mind of equanimity.