E-letter No. 80: January 2010

Dear LYWA friends and supporters,

I hope you are well. We at the Archive wish you a Happy New Year and welcome you to another year of monthly e-letters. Thank you for your interest. Please always feel free to share these with others or reprint the teachings in your own center’s newsletter etc. Thank you so much.

Books and DVDs in the Works

We’re in the process of sending out our latest new free book, Lama Zopa Rinpoche’s Kadampa Teachings. All LYWA Members and Benefactors automatically get our new books and Members also receive any Lama Yeshe or Lama Zopa Rinpoche book published by Wisdom Publications. So at this time all LYWA Members will be getting Rinpoche’s Wholesome Fear as well.

Also, due to the generosity of our supporters, we have reprinted Geshe Jampa Tegchok's The Kindness of Others. We won't be sending this out automatically, so if you'd like a copy you can order it from our website.

We’re also planning a couple more books this spring: Lama Yeshe’s Life, Death and After Death and Lama Zopa Rinpoche’s How to Practice Dharma: Abandoning the Eight Worldly Dharmas, edited by our Publishing the FPMT Lineage Editor Gordon McDougall. You can read excerpts from How to Practice Dharma on our website, and you can find another excerpt included as this month's teaching below. If you would like to sponsor the publication of this book, please let me know.

We are also working on DVDs of Life, Death and After Death and Freedom Through Understanding, the book we published last year. Lots of great stuff to look forward to!

New Online Developments

Listen online to a series given by Lama Zopa Rinpoche in 2006 at Tara Institute in Australia titled "The Need for Wisdom and Compassion". The series includes teachings on lamrim, guru devotion and the qualities of the bhumis. As usual, you can read along with the unedited transcripts.

We are continuing to add many new advices to Rinpoche's Online Advice Book. This past month we've updated the Retreat Advice section, the Prison Practice Advice section, the Purification Practices section, and more.

To receive updates at least once a week with links to new teachings on our website, follow us on Facebook or Twitter.

Other News

Lama Zopa Rinpoche has kindly offered advice for those who would like to do practices for the victims of the recent Haiti earthquake and other major disasters. Thank you very much.

And a heads up to our friends in Singapore and Malaysia: I'll be travelling there from late February to early March. I am also very fortunate that my trip coincides with a visit by Rinpoche to Amitabha Buddhist Centre in Singapore for a series of teachings and initiations. If you are in the area, I hope to meet up with you then. Please let me know: [email protected]

Much love,

Nick Ribush

Director

Discovering the Meaning of Dharma

Attachment to the happiness of this life is the cause of all our problems. It is the cause of every individual person’s problems, every family’s problems, every country’s problems; it’s the cause of all the global problems. The basic problems facing young people, teenagers, middle-aged people, elderly people—every problem we can think of—can be traced to this root, the attachment to the happiness of this life. If we could read our own life story and all the pain we have gone through so many times in this life alone, it would be like a commentary on the shortcomings of desire, our attachment to sense pleasures.

The basic message of Buddhism is to renounce the thought of the eight worldly dharmas, the mind grasping at the four desirable objects and feeling aversion for the four undesirable objects. The thought of the eight worldly dharmas is the mind that is solely concerned with the happiness of this life and any action done purely for this reason, even if it is meditating or praying, becomes nonvirtue. This is the very first thing we need to understand when we study Dharma, the very first thing we need to wake up to. Even in the Tibetan monasteries, where monks and nuns gain so much Dharma knowledge though debating and memorizing thousands of root texts and commentaries on very profound subjects—hundreds of thousands of texts!—they can still fail to discover this fundamental and crucial point.

Knowing what is Dharma and what is not Dharma—knowing the difference between holy Dharma and worldly action—is the most important thing we can do at the beginning of our spiritual journey, otherwise we can live in ignorance and cheat ourselves for our entire life.

Many years ago during the one-month Kopan meditation courses1 I used to spend a lot of time teaching about the thought of the eight worldly dharmas. I would spend weeks talking about it, finishing of with the hells, like ice cream with a cherry on top. The thought of the eight worldly dharmas is like the ice cream and the hells are like the cherry. The eight worldly dharmas used to be my main hobby in the early Kopan courses! I think I’m a little bit selfish, spending so much time talking about the subject I’m so interested in.

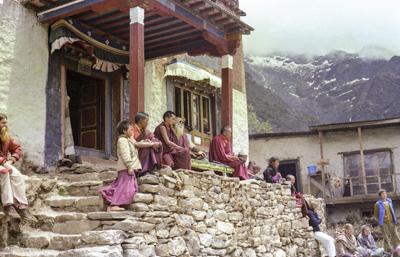

Now, of course, it is not like before. I have totally degenerated. Compared to that time I have become absolutely lazy, but at that time I was able to do many things. One thing I did regularly at that time was to go to Lawudo in the Himalayas, close to Mt Everest, to supervise the building of the Lawudo Retreat Center.

The one who lived there previously, called the “Lawudo Lama,”2 must have had a lot of energy—he received the initiations of so many practices, and teachings on the methods to achieve deities. He was a ngagpa3, not a monk, and Tibetan, not Sherpa like me and the people of the area. He lived above Namche Bazaar in the cave behind Khumjung, on the other side of the mountain from the cave where the footprint of Padmasambhava—the great being who brought Buddhism to Tibet—and syllable AH spontaneously appeared.

Before I left for Tibet, the Lawudo Lama’s son had told me he would return all the Nyingma texts that belonged to the Lawudo Lama to me, and when I arrived at Lawudo from Kathmandu they were there. Most of the scriptures kept there were written by hand with much effort, because in the past it was very difficult to get texts in that area. During my second visit I found a very special text.

This text, Opening the Door of Dharma: The Initial Stage of Training the Mind in the Graduated Path to Enlightenment,4 was composed by Lodrö Gyaltsen, a disciple of both Lama Tsongkhapa and Khedrub Rinpoche, one of Lama Tsongkhapa’s two spiritual sons. One of the texts normally practiced in the Nyingma sect, Opening the Door of Dharma describes the initial stage of thought transformation, or mind training as well as being a collection of the Kadampa geshes’ life stories and advice, based on their experiences, on how to practice Dharma. The main focus is on the distinction between worldly spiritual activities, showing clearly what should be practiced and what should be abandoned. The main emphasis is cutting off the thought of eight worldly dharmas. I hadn’t seen the text before that visit to Lawudo.

Not following desire is practicing Dharma; following desire is not practicing Dharma. It is as simple as that. Because the mind is a dependent arising, which means that it exists in dependence upon causes and conditions, our mind can be transformed any way we choose. It is possible to have realizations, but that had not been my experience at all.

While I was at Lawudo, I was supposed to watch the workers, to check whether they were cutting the stones to build the temple or just wasting time chatting. What I couldn’t do was read texts at the same time as supervising and as I spent most of the tine in the cave, they went mostly unsupervised. The only time I saw them was when I went for pipi, and many times they would just be idly chatting. But what could I say? I found it difficult to scold them. Somebody else might have been able to do that, but to me scolding seemed very strange.

Paying the wages also felt very strange to me because I was more accustomed to receiving money from other people as offerings. I paid the workers every day at sunset, knowing that some of them had done none or very little work that day. I was the secretary, I was the bookkeeper—I was everything. I kept the money in a small plastic suitcase and it would go down, down, down. And when it got right down, somebody would appear and it would go up again. I did that job for a little while.

Mostly I read, and what I read was Opening the Door of Dharma. Reading it caused me to look back on my life. I was born in 1946 in Thangme, a village near Lawudo. When my father was alive I think my family had a bit of wealth, but he died while I was in my mother’s womb, so all I can remember is how terribly poor our family was. There was only my mother and our bigger sister to look after my brother and my other sister. It was very cold in the winter and I remember how the whole family would be wrapped in my father’s old coat as we did not have any blankets. My mother had debts and was troubled with tax collectors so she would make potato alcohol to sell.

When I was very small I had a natural interest in becoming a monk. I pretended to be a lama sitting on the rock. I was virtually alone, so I was bored, but I had one mute friend, who was my everyday playmate. He was very good hearted and he pretended to be my disciple, taking initiations, doing pujas5, sitting on the ground, serving food by mixing earth and stones with water. Maybe we were serving food to the thousands of Sera Je monks, a preparation for what came later6. There is possibly some meaning to children’s games. I think the games children play reflect their interests and are somehow a preparation for the later life.

When I was four or five my uncle used to take me up to Thangme monastery, not far from my home, where I played and attended some of the prayers and initiations, although most of the time I just slept. I was still lay at this time. I remember sitting on someone’s lap and watching the lama’s holy face, not understanding a word. He had a long white beard, like the long-life man in long-life pujas, and a very kind and loving nature. Sitting there dozing in a lap, I had a very good, deep feeling.

Because I was naughty I had two alphabet teachers, who were also my gurus, Ngawang Lekshe and Ngawang Gendun. Ngawang Lekshe had a beard and he carved OM MANI PADME HUM7 on the rocks by the road for people to circumambulate. He would spend months carving the letters on a rock and they were beautiful.

He tried to teach me the alphabet, but when he went inside to make food the thought to escape would come to me and I sometimes used to run home, I think because I could play at home and there was nothing special I was expected to do. After two or three days my mother would send me back up to the monastery. Somebody would carry me up on their shoulders.

Because I kept escaping, my uncle sent me to Rul-wa-ling, very close to the snow mountains, and a very dangerous three-day journey. The area is regarded as one of the hidden places of Padmasambhava and around Rul-wa-ling there are many Padmasambhava caves and his throne. It is a very beautiful area.

I stayed there for seven years, only returning home once. I took the eight Mahayana precepts every morning, memorized Padmasambhava prayers and read long scriptures all day long, such as the Diamond Cutter Sutra, which I read many times. Besides mealtimes, I distracted myself any time I could, such as when I went out for pipi or kaka, playing a little bit and staying as long as I could. While my teachers cut trees for firewood in the forest, I collected twigs, which I took back to the monastery, where I lined them up as if they were my lamas, and I played music to them with two round things representing cymbals. I wasn’t actually reciting prayers from memory, but just imitating the chanting.

When I had to read all the volumes of Prajnaparamita (Perfection of Wisdom) texts and the texts people asked me to read for pujas, such as the Kangyur, I was very naughty. The many big texts belonged to the monastery, but when I read them, because I was often left alone, I sometimes drew black circles on them with charcoal. I can’t remember whether my teacher beat me for that or not.

When I was about ten years old I went to Tibet, to Domo Geshe Rinpoche’s monastery in Pagri.8 In the three years I was there, I was ordained and had to do my examination. In the mornings I memorized texts or the prayers that had to be recited at the monastery; in the afternoons I went to puja in the monastery or did pujas at the houses of benefactors. There were two volumes of texts to be memorized; I memorized one but I didn’t get to memorize the other.

By the time I did my examination, Tibet had already been overtaken by the Chinese Communists. Lhasa had already been taken and they were coming to our area, and so it was decided we should escape. Many of the monks were very frightened by the danger ahead, but I was very happy. I couldn’t see any reason to be frightened. We escaped in the middle of the night; there was a little bit of snow and a lot of mud, which sometimes sucked our legs down. It felt like there were nomads and Chinese spies everywhere, and dogs were barking, but nobody spoke. Perhaps they were all meditating. The next day we crossed the Bhutanese border and the following day the thirty or forty people in the group arrived in India.

I was in Buxa Duar9 for eight years, and during all those years I didn’t really study Dharma. I wasted a lot of time painting and learning English in my own way, like memorizing the words of Tibetan texts. One time I tried to memorize a whole dictionary. I started but could not finish.

I spent most of my time playing or washing in the river. At night the monks washed under a tap, but during the day we went to the river to wash, mainly because it was unbelievably hot. All the monks put their red and yellow robes on the bushes and swam in just their shorts. When you looked down on the river from the mountain, the robes on the bushes looked like flowers. During those years I took teachings, memorized texts and did some debating, but it was like a child playing.

Later, my debating was starting to develop when I became sick with TB. I was therefore sent to a school in Darjeeling, where I learned a lot of different subjects. I had to stay there a long time for my health.

Reviewing my whole life like this in the light of reading Opening the Door of Dharma, I could not find one single thing that had become Dharma.

While I was in Tibet, my teacher has given me a commentary on Lama Tsongkhapa Guru Yoga. He put it on the table and I read few pages but of course there was no way I could understand it at that time. So I had never read a complete lamrim10 text and never received teachings on it.

Now, all those years later in Lawudo reading Opening the Door of Dharma I could see so clearly that in all my life as a monk I had never had any real understanding of what Dharma was. More than that, I could see there was nothing I had done before that wasn’t worldly dharma! It was a huge shock!

Just reading the text made a huge difference. When I made a retreat after that, there was a big difference in my mind. I felt much quieter, much calmer; there was more peace in my mind; there were no expectations. Just by understanding what Dharma was. In that way the retreat became a perfect retreat.

I think because I understood from this text how to practice Dharma, even the very first day of retreat was unbelievably peaceful and joyful. Because of a slight weakening of the eight worldly dharmas, there were fewer obstacles in my mind, like having fewer rocks blocking a road, which meant less interference to my practice. This is what makes a retreat successful. I hadn’t carefully read the commentaries of the tantric practice of the retreat, but somehow the deity’s blessings were received because of fewer problems in my mind.

Now my mind is completely degenerate, but at that time, having thought a little about the meaning of this text, I felt really uncomfortable when people came to make offerings to me. In Solu Khumbu the Sherpas often brought offerings to the cave. They filled the brass containers they usually use for eating or drinking chang11 with corn (or whatever else they had), but after reading the text, I was scared to receive these offerings.

Doing the retreat after reading Opening the Door of Dharma showed me that, like molding dough in our hands, we can definitely turn our mind whichever way we want. It can be trained to turn this way, that way. By habituating our mind to the Dharma we can definitely have realizations. Even the immediate small change of mind that happened during the retreat was logical proof that it is possible to achieve enlightenment.

As Kirti Tsenshab Rinpoche12, holder of the entire holy Buddhadharma, says the Kangyur, the teachings of the Buddha, and the Tengyur, the commentaries by the pandits, are solely to subdue the mind. The evil thought of the eight worldly dharmas, the desire clinging to this life, is what interferes with our practice of listening to the teachings, reflecting on their meaning and meditating on the path they reveal. This thought is what makes our Dharma practice so ineffectual. The purpose of Opening the Door of Dharma and other texts like it is to completely reverse that way of thinking. These texts are therefore considered thought transformation or mind training (Tib: lo-jong) texts.

In fact, the whole teaching of the lamrim, the graduated path to enlightenment, is thought transformation. Its main purpose is to subdue the mind. This is why, when other teachings have little effect, hearing or reading the lamrim can subdue our mind.

What blocks the generation of the graduated path to enlightenment within our mind? What keeps us from having realizations? From morning until night, what stops the actions we do becoming holy Dharma? The thought of the eight worldly dharmas, the desire that clings to the happiness of this life alone. This is the obstacle that prevents the generation of lamrim realizations within our mind, from the foundation of guru devotion and perfect human rebirth13 up to enlightenment.

We need to train our mind by reflecting on the shortcomings of worldly concern and the infinite benefits of renouncing it. Especially we need to train our mind by meditating on impermanence and death. If this initial thought training is done, we open the door of Dharma. Then, without difficulty, we are able to practice Dharma and to succeed at whatever we wish to do, whether retreat or other Dharma practices. All our actions become Dharma.

This teaching by Lama Zopa Rinpoche comes from his forthcoming book, How to Practice Dharma: Abandoning the Eight Worldly Dharmas, edited from the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive by Gordon McDougall.

NOTES

1. The one-month meditation courses held at the main monastery of the FPMT, Kopan monastery in Kathmandu, Nepal, usually taught by Lama Zopa Rinpoche and a Western teacher. The first one was in 1971.

2. Lama Zopa Rinpoche is recognized as the reincarnation of the Lawudo Lama. See The Lawudo Lama.

3. A ngagpa is a lay tantric practitioner, a yogi often associated with rites and ascetic practices.

4. This text is the basis of the book The Door to Satisfaction.

5. Skt: an offering ceremony.

6. One of Rinpoche’s many projects is feeding the thousands of monks at Sera Je monastery in south India.

7. The mantra of Chenrezig, the compassion buddha.

8. Domo Geshe Rinpoche (d. 1936) was a famous ascetic meditator in his early life who later established monastic communities in the Tibet-Nepal border area and in Darjeeling. He was the guru of Lama Govinda, who wrote The Way of the White Clouds.

9. The refugee camp in the north of India where many Tibetan monks and nuns stayed when they fled Tibet after the Chinese invasion of 1959.

10. Tib: the graduated path (to enlightenment). The step-by-step presentation of Shakyamuni Buddha’s teachings considered the crucial basis of any Dharma practice.

11. Tibetan beer.

12. Kirti Tsenshab Rinpoche (1926–2006). A highly attained and learned ascetic yogi who lived in Dharamsala, India, and who is one of Lama Zopa Rinpoche’s gurus.

13. The first two lamrim topics, and therefore the first ones we need to realize. Our human existence is considered “perfect” because it has all the causes and conditions necessary to lead us from suffering.