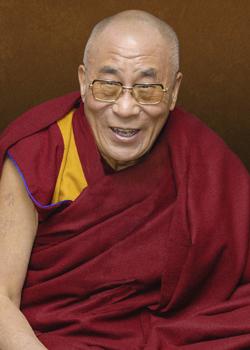

The Buddha of Compassion in our Midst

This article by Nicholas Ribush was published in Understanding the Dalai Lama, edited by Rajiv Mehrotra, published by Hay House Inc., 2009.

I first encountered Tibetan Buddhism at Kopan Monastery, Kathmandu, Nepal, towards the end of 1972. My first teachers were Lama Thubten Zopa Rinpoche and Lama Thubten Yeshe, who were just starting to introduce the Dharma to Westerners, an activity that continues apace to this day. I was immediately attracted to this path and have been trying to understand and practice it since.

From the start, Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche manifested extraordinary respect for and devotion to His Holiness the Dalai Lama and, as a cynical Westerner from a predominantly materialistic and atheistic upbringing, I was struck by their attitude towards what I imagined was simply another human being.

I was able to meet His Holiness for the first time about fifteen months later when, in January 1974, I went to Bodhgaya, India, to attend the Kalachakra initiation he was to confer. I also planned to take novice ordination, along with nine other prospective Western monks and nuns. There were well over 100,000 people there and we Westerners were lost in a vast and wonderful sea of Tibetans.

Out of his customary kindness, Lama Yeshe had requested His Holiness to perform the very first part of our ordination ceremony, where the last tuft of hair is snipped off the crown of one’s otherwise freshly-shaved head, recalling Siddhartha Gotama’s own renunciation when he left his father’s palace and set out on his quest for enlightenment. Accordingly, on the last day of the initiation, we lined up with everybody else to receive a blessing from His Holiness and view the mandala. As we approached His Holiness, Lama Zopa Rinpoche pulled out a pair of scissors and explained who we were and what we wanted. His Holiness smiled, laughed out loud, and exclaimed, “I hope it lasts!” (In my case it did, but not for life, as intended, but for only about twelve years.) That brief but warm encounter, that individual attention despite a million other things going on, was my first taste of His Holiness’s astonishing kindness, compassion, focus and love.

I met His Holiness a few more times in the next couple of years, mainly in the company of Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche, when they would seek His Holiness’s advice on their work in the West and report to him what had happened on their travels. In 1977, my mother visited me in India and I took her to Dharamsala to meet His Holiness and his two tutors, Kyabje Ling Rinpoche and Kyabje Trijang Rinpoche. They were all amazingly kind, especially His Holiness, who gave my mother a forty-five minute private interview (they let me in, too), patiently answering all her questions about past and future lives and the six realms of cyclic existence.

I have heard His Holiness described in many ways over the years. He always describes himself as a simple Buddhist monk, but to various writers he has been the God-King of Tibet; to the Chinese, a splittist; to Rupert Murdoch, a cunning old monk in Gucci shoes; to most politicians, the true head of Tibet; to Dharma students everywhere, a great teacher and a perfect, living example of what he teaches; and to the world at large, a Nobel Laureate, a great statesman, the leading advocate of nonviolence and peace, the voice of Buddhism and, in general, our best hope for the future. To the Tibetan people, His Holiness has always been the living manifestation of Chenrezig—Avalokiteshvara, the Buddha of Compassion. I’ve often wondered what this means.

While never for a moment agreeing that he is indeed a manifestation of Avalokiteshvara, in his teachings at the Kalachakra initiation in Los Angeles, 1989, His Holiness described Avalokiteshvara as a deity, a bodhisattva or a buddha. As a deity, Avalokiteshvara is not a separate being but a manifestation of the compassion of all buddhas, a quality of all enlightened beings. When a person striving for enlightenment attains his or her goal through practicing the yoga method of Avalokiteshvara, we can call that person an individual Avalokiteshvara. Also, the compassion of a particular buddha, for example, Shakyamuni Buddha, can manifest as Avalokiteshvara.

As His Holiness Dudjom Rinpoche has explained, historically, Tibetans claim to be descended from Avalokiteshvara, who in ancient times is said to have come to Tibet from his reputed abode in South India, Mount Potalaka, manifested as a monkey and mated with an “ogress of the rocks.” The first religious king, Songtsen Gampo (617—650) is said to have been a manifestation of Avalokiteshvara. So, too, are Nyatri Tsenpo, the first human king to rule the whole of Tibet; Drom Tönpa, translator for the great Atisha, who restored pure Buddhism to Tibet about a thousand years ago and founded the Kadam tradition; and all fourteen Dalai Lamas, including, of course, the present one, His Holiness Tenzin Gyatso, the Fourteenth Dalai Lama of Tibet.

Also, the mantra of Avalokiteshvara, OM MANI PADME HUM, is the “official” mantra of Tibet. Many Tibetans, both lay and ordained, recite it constantly, and it may be found painted and carved into rocks and stone tablets all over the Himalayas.

Thus, the practice of Avalokiteshvara is central to Tibetan Buddhism and as a part of that, Tibetans regard their spiritual and temporal leader, the Dalai Lama, as the living embodiment of Avalokiteshvara and everything he represents.

The Buddha’s intent was that all sentient beings attain enlightenment. In order to do so, sentient beings have to follow the path that leads to enlightenment; we have to make the effort ourselves—the infinite buddhas cannot do it for us. In other words, we have to practice Mahayana Buddhism, and, if we want to attain enlightenment as quickly as possible, we have to practice Vajrayana, the form of Mahayana Buddhism that was practiced and preserved in Tibet.

His Holiness also said that of all the Buddha’s teachings, the most important is that on compassion, and of all the qualities of a buddha, the best is again compassion. Even a buddha’s omniscience depends on compassion; it is only through the power of compassion that it is possible for the wisdom realizing emptiness to become the ultimate wisdom of a buddha. Furthermore, the exalted activities of a buddha arise through the union of pure mind and pure body. These, in turn, similarly depend upon the wisdom that is empowered by compassion. Thus, again, compassion is crucial.

As the great Indian pandit Chandrakirti declared, compassion is important at the beginning, in the middle and at the end. All the great qualities of a buddha have their root in compassion.

In a praise to His Holiness, Lama Zopa Rinpoche said, “Your Holiness is able to preserve the complete teaching of the Buddha, the three higher trainings of morality, meditation and wisdom, the three baskets of teaching, which are the essence of the Hinayana teaching and the foundation of the causal Mahayana Paramitayana path and the resultant secret Vajrayana, which flourished in the past in Tibet and now even outside Tibet.

“Because of that you are able to produce continuously many hundreds of thousands of holy scholars and highly attained yogis, like stars in the sky. Even nowadays in different parts of the world, large numbers of people are able to receive many highly qualified practitioner-teachers from the monasteries of Sera, Ganden and Drepung and also from the monasteries of the other Tibetan traditions. Thus, many Westerners are able to learn whatever they wish from them in depth and in this way are able to make their lives meaningful by putting these teachings into practice, finding fulfillment in this way. They have so much opportunity to enjoy peace and happiness and are able to direct their lives toward liberation and enlightenment, and this is increasing every year.

“This is solely due to Your Holiness’s kindness. This means that without Your Holiness, Buddhism would suffer and it would be extremely difficult to continue the preservation of the entire Buddhadharma. Without the teaching, sentient beings would suffer. The teaching of the Buddha is the only medicine to cease all the diseases of delusion and negative karma and their imprints….

“A special quality of Your Holiness that ordinary people can see and feel is that even though there might be some evil beings who criticize Your Holiness, but, differently from common people in the world and even other religious leaders, you only benefit them in return and you have greater compassion for them and cherish them most in your heart. You speak about their qualities and only pray for their well-being and temporary and ultimate happiness up to enlightenment. This means that there is no doubt that Your Holiness is a bodhisattva, the Compassion Buddha.”

What are the activities of a buddha? The main activity of a buddha is to reveal the teachings that lead to enlightenment to those who are open to them, that is according to the karma of potential disciples. First, however, how does one become a buddha? How does one become enlightened?

As I understand from the teachings of my own precious teacher, Lama Zopa Rinpoche, the principal cause of enlightenment is bodhicitta, the determination to reach enlightenment for the sake of all sentient beings. Bodhicitta arises from great compassion, which is generated in dependence upon each and every sentient being. With great compassion, one not only feels the suffering of all sentient beings as one’s own but is also compelled to do something about it. This feeling only grows as one approaches enlightenment and remains with one forever, even after enlightenment. Therefore, a buddha has no choice but to help sentient beings in whatever way possible.

Since sentient beings have to make the effort themselves, they need to be shown the path. Showing the path and inspiring others to follow it is a buddha’s main job. But, if one were a buddha, how would one go about it?

One couldn’t remain in the enlightened sphere of the Dharmakaya, because there, one could communicate with only other buddhas. One could manifest in the Sambhogakaya, but only advanced bodhisattvas can be taught at that level. Instead, one would have to manifest in a form with which lower beings could communicate. However, very few sentient beings have the capacity, let alone the interest, to practice Dharma, so one would have to manifest among those who do—in other words, as a human.

Manifesting among humans, one could appear in some kind of miraculous form, like a rainbow body, but while that would attract attention, it wouldn’t really be of that much benefit. People need to be inspired to follow the path to enlightenment by being able to see that they, too, can become enlightened. To inspire people in this way, one would have to manifest in a form they can relate to—as a person. Then people can think, “I’m a person; she’s a person. I can become like her.” In that way, they open themselves to the teaching. Thus, if the people on Earth at this time were open to benefit, one would manifest as a human teacher.

But “manifest” doesn’t mean simply to appear as some kind of magical creation; it means to direct one’s enlightened consciousness into the products of a suitable human conception, whose future parents’ sperm and egg have just conjoined to form an embryo, and to take birth as a human baby nine months later.

Watching His Holiness, even from afar, as I’ve had to do, it’s easy to see how he could indeed be the living embodiment of an enlightened consciousness. He radiates love and compassion; everybody wants to be near him all the time. His wisdom is also clearly apparent—he can teach a range of students from rank beginners to highly learned geshes and advise the most sophisticated hermits in retreat. He takes responsibility not only for his land and his people, Tibet and the Tibetans, but also for the whole world, striving constantly to bring peace, reason and understanding to as many people as he possibly can. His Holiness travels tirelessly, meeting and inspiring world leaders, ordinary people and Dharma students everywhere.

Day after day, His Holiness extends himself as much as any man on Earth, but all for the benefit of others. He is constantly traveling the world, teaching Dharma and giving initiations, holding audiences for all manner of visitors, meeting politicians, giving speeches and press conferences, appearing at this function or that, participating in conferences and so forth. From morning to night, in Dharamsala and abroad, His Holiness runs from one appointment to the next, taking great responsibility every time—responsibility for the spiritual welfare of not only the sentient beings on this planet but also countless others throughout all of space; peace on Earth; the welfare of Tibetan refugees and the oppressed people in Tibet; and the very freedom of Tibet itself.

I don’t see His Holiness all that often, perhaps a few days each year, but every time, I feel exhausted just watching how busy he is, how constant are the demands on his time and how amazing is the energy he puts into each and every person he meets.

His Holiness never forgets the unimportant people, either. Once I was at an event in Indiana, where His Holiness was consecrating a stupa built by his elder brother, Taktser Rinpoche. Everybody was lined up, three deep, along the path; I was at the back somewhere. I’d disrobed a year previously and hadn’t seen His Holiness since that time. As His Holiness moved down the path, looking back and forth at the people on either side, he noticed me, slightly bent over, hands folded at my heart. In Tibetan, he called out, “What happened to being a monk?” or words to that effect, and swept on. I was amazed—that he would see me, remember who I was and that the last time we met, more than a year before, I was a monk. He also knew that I wasn’t just wearing lay clothes but had actually disrobed.

Ten years later, His Holiness was visiting Brandeis University, in Boston. Moving rapidly from one meeting to the next, His Holiness, surrounded by security, was walking through a crowd of people, smiling at everybody he could, when again he saw me, bent over, about twenty yards away. “Old friend,” he called out, motioning me to come over; “Old friend.” I was so touched that in all this busyness he would be so kind. And of course, it’s not just me. His Holiness is like this with most people he knows, and he knows so many.

Surely His Holiness the Dalai Lama is the Buddha of Compassion. Who else would have the wisdom, power and compassion to accomplish all that he does? Of course, I wouldn’t even pretend to see or know but a fraction of what His Holiness does for others, but anybody who observes him with clear sight and an open mind will see more than an extraordinary person among us.

References

His Holiness the Dalai Lama, The Thirty-seven Practices of the Bodhisattva. (Audiotape.) Translated by Jeffrey Hopkins. Los Angeles: Thubten Dhargye Ling, 1989.

Dudjom Rinpoche, Jikdrel Yeshe Dorje, The Nyingma School of Tibetan Buddhism. Boston: Wisdom Publications, 1991.

Lama Zopa Rinpoche, “The Compassion Buddha is no other than Your Holiness.” From the praise and request offered to His Holiness after the Kalachakra initiation in Sydney, Australia, September 1996. Reprinted in Mandala Magazine, November—December 1996.