Birth of a Buddhist Publishing Company

This article by Nicholas Ribush about the growth of Tibetan Buddhist publications in the West appears in Renuka Singh's anthology The Path of the Buddha: Writings on Contemporary Buddhism. Links to many of the publications mentioned in this article can be found below.

The Path of the Buddha book was first published by Penguin Random House India in 2003. The book contains essays by spiritual leaders like His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Lama Zopa Rinpoche and Lama Thubten Yeshe, as well as the accounts of others who have embarked on the Buddhist path.

It was January 1977 when Lama Yeshe called me into his room atop Kopan Monastery and said, “I think we need a center in Delhi. I want you to go there and start one.”

This came as a bit of a shock to me, as I was just settling into my fifth year at the monastery and had no desire to be anywhere else. But perhaps that was the problem. Lama didn’t like anyone to get too settled. As he often used to say, “There’s no security in cyclic existence. Everything always changes.” This was a basic fact of life to which I could assent intellectually but preferred to ignore. If there was one thing Lama always tried to combat, it was ignorance.

Why was I surprised? Most of my Western colleagues at the monastery—both lay and ordained—were being sent hither and thither to staff Lama’s growing organization of centers in the West, the Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition (FPMT). Why should I be any different? But this was not the West to which I was being sent; it was India.

The reason Lama wanted a center in Delhi, he went on to explain, was that for centuries, the Tibetan people had benefited from that greatest of all Indian gifts to the world, Buddhadharma, and now that Buddhism had all but disappeared from India, it was time to repay the kindness of the Indian people by helping bring it back home. Reflecting on this, I could see that since I, too, was benefiting from Buddhism, I also had some kind of obligation to India.

Of course, the obligation of the Tibetans towards India did not extend only to Buddhism. In 1959, the failed Tibetan uprising against China’s brutal occupation of Tibet had forced more than one hundred thousand people into exile; India had kindly offered most of them a safe refuge from death, torture and terror.

But all that notwithstanding, Lama was my guru, so there was no way I could balk at his request.

Life before Dharma

Born in Australia in 1941, I grew up in a comfortable middle-class family, was educated at a private school, graduated in medicine from Melbourne University in 1964, and worked in a variety of mainly hospital jobs for seven years before taking off on what was supposed to be four-year trip around the world with my girlfriend, Marie. There was nothing in this background to suggest what was to come.

My family was Jewish by descent but atheist by religious persuasion. When Christian friends at school tried to convert me, my mother gave me Bertrand Russell’s Why I am Not a Christian to read. That kind of upbringing and the scientific training I received as a medical student conspired to make me a scientific materialist. If I thought about larger issues seriously at all, and I didn’t much, I guess I believed that the universe had evolved through a random series of chemical events, we were all here by chance, and one life was all we got. In my circle, the big questions—Why are we here? What is the purpose of life?—were usually asked in the context of jokes.

At a certain point in my career, I began to become disillusioned by the way medicine was being practiced. Four years into my training as a general physician I had decided to specialize in kidney disease. In the 1960s, dialysis and transplantation were relatively new and interesting developments; job opportunities in this pioneer field were opening up. As soon as I started working in this area, I noticed that many, if not most, of the patients presenting with renal failure were suffering from analgesic nephropathy—irreversible kidney damage due to the ingestion of excessive amounts of painkillers. These tablets and powders that destroyed people’s kidneys and upon which people became heavily dependent were not only freely available over the counter without prescription but were heavily advertised. This seemed bizarre to me.

As I then reflected upon my several years of hospital practice, I realized that more than fifty percent of the patients I’d seen were ill because of tobacco and alcohol—more toxins that were not only freely available but also heavily advertised. The conclusion I came to was that if, as a doctor, I really wanted to improve people’s health, getting them to stop smoking, drinking and taking analgesics—at least to the point where these substances began to damage their health—would be a great start. However, such an effort would have to begin by stopping advertising.

When I looked into what would be involved in stopping the advertising of legal drugs, the inescapable conclusion to which I came was that I’d have to get out of medicine and into politics. This was such a distasteful option that I started to get a little cynical about medicine. I felt that doctors were little more than boxers’ seconds, those guys in the corner who patch up the boxer in between rounds and then throw him back out into the ring to get beaten up again. Patients would come reeling into our clinics from the ring of life, and all we could do was offer them was some temporary relief and then send them back out into the same circumstances that made them sick in the first place. The futility of all this made me decide to take a break and get some perspective.

Leaving Australia

It took a while to organize, but a year or two later, Marie and I set off on our extended trip around the world. We spent a couple of months relaxing on the beach in Bali, then headed north through Indonesia and beyond. A few weeks later, in Thailand, I began to see many of the external manifestations of Buddhism, such as monks and temples, and decided, as a dutiful tourist, to read more about Buddhism, in order to understand better the culture of the country through which I was traveling. The book I picked up was a Pelican paperback called Buddhism, by Christmas Humphreys, the English judge who had founded London’s Buddhist Society in 1924.

Now, I wouldn’t necessarily recommend this title to anyone today, but for me, it was the right book at the right time. I didn’t actually get into it until we had reached Laos and were languishing in Vientiane in one of the countless cheap guesthouses that dotted the hippie trail in those days. As I read about the Buddhist topics of karma and emptiness, a strange, unfamiliar sensation stirred in my heart, and the thought arose, “This is really true.” What I was reading seemed completely authentic; not in the factual sense of an anatomy textbook but in a far deeper way, where knowledge is more felt than thought.

The feeling passed soon enough, but not before I had made a mental note to find out more about meditation, which the author had emphasized to be an essential element of Buddhist practice.

After a week or so in Laos, we returned briefly to Thailand and then spent a week in Burma, where we were again exposed to many outer expressions of Buddhism: mountain after mountain topped by gleaming white stupas, the wonderful Mandalay Hill and the breathtaking plain of Pagan. After that, we went to Calcutta, where I picked up a couple more books on Buddhism from the Mahabodhi Society. However, our destination was Kathmandu, where we had arranged to meet a Danish guy we had befriended in Bali. I had lent him the money for a trip home to Copenhagen, and we’d agreed to meet in Nepal so that he could repay the loan.

When we got to Nepal, the Danish guy was nowhere to be found, but we ran into a Brazilian friend whom we’d also met in Bali. While showing us around Kathmandu, he mentioned that a one-month meditation course was about to start at the small monastery of Kopan, just outside of town. We decided to give it a shot.

The Kopan meditation course

The Kopan course was amazing. There were about fifty Westerners there, most of whom had not taken Buddhist teachings before. This was actually the third such course that Lama Zopa Rinpoche had given at Kopan over the past couple of years and some of the students present had attended one or both of the previous ones, but most of us were new. The day began early, around five o’clock in the morning, with a ninety-minute meditation. Those of us who had not sat before found it hard on our backs and legs, but we persisted. After breakfast, Rinpoche would teach for two or three hours and again for a couple of hours in the afternoon. There was also a discussion group after lunch and another meditation in the evening, before we went to bed. All in all, these were sixteen-hour days full of unfamiliar activities: sitting in meditation, listening to weird ideas, eating strange food, going to bed early and getting up even earlier.

The first thing that impressed me was Lama Zopa Rinpoche himself. Almost twenty-seven, he was relatively young in years, but seemed ancient in wisdom. Teachings flowed effortlessly from his mouth, punctuated frequently by peals of loud, high-pitched laughter, which invariably electrified the room and made most of us laugh out loud as well. Day in and day out, a seemingly inexhaustible ocean of new and challenging revelations shook my world and made me question everything I had ever believed.

Rinpoche taught from a locally-produced book that we’d been given upon enrollment, The Wish-Fulfilling Golden Sun of the Mahayana Practice, which had been put together, not particularly well, to my critical mind, by students from previous courses. It had been printed on an old duplicating machine from wax stencils that had been cut on different typewriters, had a rough, rice-paper cover, and was tied together with what looked like a shoelace. But what this manual lacked in production values, it more than made up for in content. The Humphreys book might have set me in this direction, but the Golden Sun really changed my life.

Rinpoche would read a sentence or two from the Golden Sun and then offer a commentary that could be as brief as a few minutes or last a few days. In the meditation periods we would analyze what we’d been taught. There were many ideas that were completely new to me—beginningless mind, mind separate from body, reincarnation, the six realms of cyclic existence, refuge in Buddha, Dharma and Sangha, karma, liberation and enlightenment—and we listened, thought and meditated on them all. Most of these topics were hard for me to accept at first, but many other teachings were immediately accessible, particularly those on Buddhist psychology. When Rinpoche explained the division of the mind into six primary consciousnesses and fifty-one mental factors and we had to look into our own mind to recognize these aspects of it, I felt I was learning more about myself than I’d learnt in my entire life up to that point. As Rinpoche once said, “The purpose of this course is to introduce you to yourself.” (You can read the transcript from Kopan's Seventh Meditation Course in 1974 here.)

Buddhism

I was also impressed by the Buddhist approach. It was more scientific than science. First, it offers a framework for considering everything that exists. Existent phenomena are either permanent or impermanent; impermanent phenomena are divided into form, consciousness or neither; these categories are subdivided further and further, and in the end, there is nothing that is not addressed and explained by the Buddhist worldview. Furthermore, we were not expected to accept it because “It’s in the Book.” As the Buddha himself said, “What I say is true, but don’t believe it just because I said so. Analyze my teachings and prove them true for yourself.” By the same token, we were allowed to reject what the Buddha taught. We just had to prove the teachings wrong.

In all this, there was no creator God. I’d always imagined Buddhism to be a religion like the rest—Christianity, Judaism, Hinduism, Islam and so forth. The problem I’d always had with this was that if the all-powerful and all-loving God had created everything, why was his creation so imperfect. Why was the world filled with ugliness and suffering. Where had he gone wrong? Why trust such an amateur? I’d concluded by thinking that God was a fabrication of people’s imagination, a crutch for weak people, and anyway, there was no proof whatsoever for his existence. Even as a teenager, I could see a huge disparity between what Jesus taught and how his supposed followers behaved. I used to think that if what the Bible taught was correct, how could believers not devote themselves completely to the practice? But clearly, they did not.

Rinpoche once asked, “Why did God need to create anything?” That was a good question. Was he bored? Dissatisfied? He also said, “If God created everything, he must be responsible for all the suffering we find. The way to eradicate suffering is to destroy its cause. This means that you’d have to destroy God, which is a nonsensical conclusion, but one that inevitably arises.”

Thus, I found, Buddhism is a religion without God. Everything is created by mind; mind is beginningless; our world and the beings in it are created by delusion and karma; delusion and karma come from an erroneous perception of reality; this perception can be corrected, resulting in complete liberation from suffering and everlasting peace and bliss; the purpose of making this correction is not only to benefit oneself but, more importantly, to benefit all living beings. This is why we are here; this is the purpose of life. That seemed to be a much better way to go.

I used to hear about miracles and laugh. But here, at Kopan, I found a miracle: the graduated path to enlightenment. Shakyamuni Buddha taught for more than forty years, but there was no particular structure to the way he taught. Like a good physician, he dispensed whatever medicine the suffering sentient beings in front of him could digest and needed at the time. When you stop and look back at the entire body of Lord Buddha’s teachings, they’re all mixed up—high, low and medium. Which are for me? How do I put these into practice? How do I progress?

A thousand years ago, the great Indian monk, scholar and yogi, Dipamkara Shrijnana (Jowoje Atisha), came to Tibet, and in order to reintroduce the fundamentals of Buddhism to the Tibetan people wrote a simple text called A Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment. In it, he organized all the teachings of the Buddha into a simple, straightforward step-like path that anybody could understand. This is the miracle—that there exists a roadmap to enlightenment. You can look at the outline of the path and see where you are, where you are going, and what you should do next. This is the genius of Tibetan Buddhism, and Rinpoche’s Wish-Fulfilling Golden Sun was based on the great Atisha’s teaching.

Basically, the entire path to enlightenment is divided into three, according to the practitioner’s level of motivation. Those who are simply interested in avoiding rebirth in the hell, hungry ghost or animal realm follow the teachings of the lower scope. Those interested in complete liberation from the whole of cyclic existence follow the teachings of the intermediate scope. Those interested in enlightenment for the sake of all sentient beings follow the teachings of the highest scope. Within the three scopes are literally thousands of meditation topics, each to be understood, thought about and meditated upon in the correct order, just as one passes through one town and then the next when going on a long journey.

Rinpoche taught us that motivation is everything; it is motivation that determines whether an action will be positive—the cause of happiness—or negative—the cause of suffering. It is motivation that demarcates Dharma from non-Dharma. If we were to take only one thing from the course, he said, it should be that the principal cause of happiness and suffering lies within, in our own minds, not externally, in the material world or other people.

Lama Yeshe

One morning during the course, I was approached by Anila Ann McNeil, the tall Canadian nun who was assisting Lama Zopa with the course. She said, “They tell me you’re a doctor?” I agreed and she asked me follow her to see “Lama.” I didn’t know whom she meant, as Rinpoche was the only lama we’d seen so far. Apparently this Lama had barked his shin on a glass-topped coffee table and the wound had gotten infected.

I was greeted by an incredibly warm, smiling Tibetan monk, saying, “Thank you so much, dear; thank you so much.” I wasn’t aware of anything that I’d done that deserved his thanks, but I guess I said “No worries” or words to that effect and took a look at the wound. I decided that the best course of action would be to give Lama Yeshe, for that is who it was, penicillin injections, which would have to be brought up from Kathmandu. Accordingly, the next day, I went back to see Lama to give him his injection. I swabbed his skin, rolled the syringe between my hands to loosen the penicillin up, thrust the needle into Lama’s buttock and pushed down on the plunger. Unfortunately, I’d made the cardinal error of not tightening the join between the needle and the barrel of the syringe, so that they popped apart, leaving the needle quivering in Lama’s flesh and penicillin all over the room.

I was extremely embarrassed by this display of ineptitude, but Lama simply smiled, thanked me again and said, “Let’s try again tomorrow, dear.” That was how I met my guru.

Getting into publishing

After the third Kopan course had finished, I did a short retreat and then offered my services to Rinpoche in revising the Golden Sun—to improve its English and set it out more clearly, the better to make the teachings in the book accessible to all and share my experiences with others. Surprisingly, Rinpoche agreed, and over the next couple of months, Marie, who had received the refuge name of Yeshe Khadro and would be known henceforth as YK, and I spent every day with Rinpoche, working through the book, rewriting it from cover to cover. By the time the fourth Kopan course arrived, in the spring of 1973, the new edition was ready, with an expanded title: The Wish-Fulfilling Golden Sun of the Mahayana Thought Training: Directing in the Shortcut Path to Enlightenment. During this time, we had also reorganized the Kopan library and set up a free medical clinic for the Kopan monks, local Nepalis and Western Dharma students, using medical supplies that had been sent to me by friends and colleagues in Australia.

That summer, a few of us went up into the Himalayas, to Rinpoche’s monastery at Lawudo, not far from Mt. Everest. YK and I set up a small free clinic for the local people, but the main thing I did was edit my own and another student’s notes of Rinpoche’s commentaries on the Golden Sun from the third and fourth Kopan courses, in order to produce a companion volume to the root text. While doing this, I felt more acutely than ever how precious Rinpoche’s teachings were and how much we’d missed by simply taking cursory notes. Therefore, I resolved not to miss a word of the next course, the fifth, in the fall of 1973.

Working on Rinpoche’s teachings on the perfect human rebirth, with its eight freedoms and ten endowments, it became very clear to me how precious my life and the Dharma were, and how the best way for me to completely devote myself to the practice would be for me to become a monk. At first I was a little taken aback by the conclusion to which I’d come, but after I made a list of pros and cons, in which there were plenty of pros and not a single con, I told YK I was thinking about getting ordained. She was a little taken aback herself, but, with some reservations, accepted my decision.

After we got back from Lawudo for the fifth Kopan course, in the fall of 1973, I asked Lama Yeshe’s permission to become a monk, and he said yes. As it turned out, YK had also decided to take ordination, as had eight other Western students at the course, and along with Lama Zopa Rinpoche’s mother, we were all ordained at Bodhgaya in January 1974.

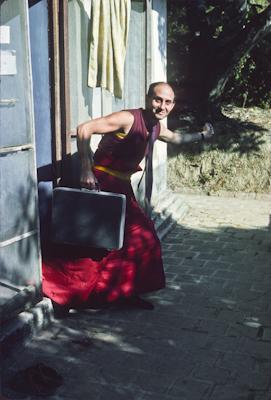

After the fifth course, Rinpoche and I had done more work on the Golden Sun and now that, as well as the two volumes of commentary that I’d edited, needed to be printed, so I asked Lama Yeshe if we could buy our own Gestetner duplicating machine for Kopan. Surprisingly, he agreed, and thus we began our own little printing operation at Kopan, producing not only teachings for Western students but also many Tibetan texts for the growing community of Nepali and Tibetan monks at the monastery. We didn’t know it then, but this little enterprise was the seed of what would become one of the world’s leading Buddhist publishing houses, Wisdom Publications.

The Dharma goes West

In the summer of 1974, Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche made their first trip to the West, teaching in the USA, Australia and New Zealand. Kopan courses, which had been held twice a year, were now conducted only annually, every fall. After the eighth Kopan course, at the end of 1975, Lama Yeshe was approached by an American Dharma student, Jesse Sartain, who ran Conch Press, a small publishing house in Hawaii. He asked Lama if he could publish the teachings the Lamas had given in the USA the previous year. Lama Yeshe called me over to discuss the project with Jesse, instructing me not to give anything away but for Jesse and Kopan to publish the book together. This we did, and the next year our first real book, Wisdom Energy, was born, and along with it, our publishing company, Publications for Wisdom Culture.

In 1976, Lama Yeshe was offered a manuscript by a New Zealander, Brian Beresford, who’d been studying in Dharamsala and had translated a couple of teachings by Geshe Rabten and Geshe Ngawang Dhargye. We decided to publish these teachings in Delhi, and called the book Advice from a Spiritual Friend, Publications for Wisdom Culture’s second book.

In those early years, it was very hard to find a decent English-language Dharma book, especially in our tradition, the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism, the tradition of the Dalai Lamas of Tibet. Of course, many Buddhist books had been published, but few were on Tibetan Buddhism, and most of those that were had been written or translated by Western scholars who basically didn’t know much. When I look around now and see the thousands of Buddhist books that are now available by highly realized and learned masters and practitioner translators, I can scarcely believe it. Not only are specialist publishing houses like Wisdom, Snow Lion and Shambhala putting out scores of Dharma books each year, but also big, mainstream publishing houses are competing fiercely with each other to secure titles by His Holiness the Dalai Lama, other lamas, and many Western authors as well. Of course, here in this article, I am considering only books in the English language.

The evolution of Wisdom

I started this story with the news that I was being sent to Delhi to start Tushita Mahayana Meditation Centre, and that’s where we now find ourselves. Since I was going to be in Delhi, Lama thought we should also base Publications for Wisdom Culture there, and sent the newly ordained Australian nun, Robina Courtin, to help me. Robina’s family had owned a printing business and she’d also gained publishing experience working with the London publisher André Deutsch. While I busied myself looking for a suitable house in which to start Tushita Mahayana Meditation Centre, Robina started researching typesetters and printers.

It took me a couple of years to find our first, beautiful house, in Shantiniketan, New Delhi, but in the meantime, Lama had decided to locate his publishing house in the West, and in 1978, Publications for Wisdom Culture moved into its new home at Manjushri Institute, Cumbria, England, and changed its name to Wisdom Publications.

Unable to control my editing and publishing inclinations, I soon established a publishing activity at Tushita—Mahayana Publications—and over a two-year period we published a number of books, including the anthology, Teachings at Tushita; Gareth Sparham’s Tibetan Dhammapada; and a number of smaller booklets. These activities proved disconcerting to some of the people at Wisdom Publications, which by 1981 had established its business office in London, while maintaining editorial, production and distribution in Cumbria. When they complained to Lama Yeshe that I should be working for Wisdom instead of creating another FPMT publishing entity in New Delhi, Lama responded by appointing me Wisdom’s editorial director, but kept me in India directing Tushita.

At that time I was also in the process of organizing Lama’s first Enlightened Experience Celebration—a convocation of the International Mahayana Institute (the organization of Lama’s Western monks and nuns) and FPMT lay practitioners—to be held in Bodhgaya and Dharamsala. During the five-month event I advertised for potential editors—people willing to attend a retreat where they would be trained to edit Lama Yeshe’s teachings by our best editor, Jon Landaw, who had edited Wisdom Energy.

Accordingly, after Lama’s 1982—83 teachings on the Six Yogas of Naropa in Italy, six of us got together with Jon at a seaside resort near Pisa for a couple of months to see what we could produce. Each of us took on one of Lama’s commentaries to edit under Jon’s supervision. The experiment was not a great success, but eventually two books came out of it, Introduction to Tantra (1987), edited by Jon and The Tantric Path of Purification (1994), edited by me.

Towards the end of the editing retreat, in February 1983, the director of Wisdom Publications came to see Lama to offer his resignation, and Lama asked me to take over. After five years in Nepal at Kopan and six in India as director of Tushita, I’d finally be leaving the East. I had mixed feelings about it. On the one hand, I’d very much enjoyed those eleven years and knew it was going to be much harder to be a monk in England than it had been in India and Nepal, but on the other, I would once again be taking charge of FPMT publishing, with which I’d been so closely involved from the beginning.

The big problem was that we had no money. My predecessor was a businessman who’d used his company’s profits to finance Dharma publishing, and he ran Wisdom part-time. Moreover, some of the money that he’d put in was a loan; along with Wisdom, I was inheriting significant debt. In addition, there were a number of signed contracts committing us to publish several books that year. I had no income or savings, and because of serious problems with the people at Manjushri Institute, we could not base Wisdom there, as Lama had wished, but had to set up in London, which was not only “not a good place for monks and nuns,” as Lama put it, but also very expensive.

The first thing I did was to take a trip to Australia and the Far East in search of funding. At first I thought I’d be able to get donations, but Wisdom, which at that point had published only about six books, did not have enough of a track record for wealthy people to want to fund it. In the end, I borrowed about $30,000 from family and friends and, after a brief trip to Shantiniketan to bid farewell to my many kind Indian friends and get my stuff, I went back to London to see what we could do.

There were three of us there—my former girlfriend, YK (who left after a few months), Robina (who’d moved to England with Publications for Wisdom Culture in 1978) and me—living and working in a tiny flat just off Baker Street, in London’s West End. Our plan was to bump up production so that we’d be publishing at least eight books a year, which, if they sold well enough, would give us enough income to cover our expenses. Of course, we ourselves were not getting paid—just a place to live and our food. Our major effort that year was to publish Jeffrey Hopkins’s classic Meditation on Emptiness, a 1,000-page work that was financed by a $20,000 interest-free loan (all our loans were interest-free) from an American Dharma student.

However, it very soon became clear that publishing a book is one thing; selling it is another. Bigger publishers often depend on a few best sellers to finance the rest of their list; academic presses are subsidized by the university with which they’re associated. We could never see ourselves publishing a Dharma bestseller—certainly not back then—because in most cases, bestsellers are not born, they’re made, and we had no university to back us. To bring one of our books to the attention of enough buyers, we’d have had to spend more than our entire annual budget marketing it. To get our books into bookstores, we enlisted the services of a distributor, but the discounts were so heavy that there was hardly anything left for us. We realized that to counter this, we would have to sell a good proportion of our books at retail price ourselves, so we set about establishing our own mail order service, to supplement distributor sales.

Once we had established the infrastructure to sell our own publications directly by mail order, we took on other publishers’ Buddhist titles to generate extra income. We soon realized that offering a wide range of Dharma books was actually a great service to the Buddhist community, as most bookstores carried few Dharma books, and we decided that our mail order catalog should contain every authentic English-language Buddhist book in print. Even though Wisdom Publications itself would undergo many changes, this excellent mail order service lives on in England under the name of Wisdom Books.

As well as deciding to offer a wide range of Buddhist titles by mail order, we also made the publishing decision to branch out from Tibetan Buddhism and represent all true Buddhist traditions in our list. In order to maintain our high production standards—which we later heard were the envy of editors at some of the mainstream publishing houses—without spending too much money, we started printing our books in Singapore.

Early in 1984, we doubled our staff with another editor, a bookkeeper and a marketing manager, and moved into a large family residence in Streatham, a south London suburb. We each now received an allowance of about $10 a week as well as food and board. We published several more books, some prints and postcards and our first mail-order catalog. We also found an American distributor in an attempt to penetrate the world’s biggest market for Buddhist books. However, with even bigger discounts, increased shipping expenses and still not particularly great sales, we continued to find it impossible to break even, so I started focusing more energy on fund raising.

I wondered how other publishers trying to do what we were doing were managing. There weren’t that many to look at. Shambhala Publications, which had been started by students of Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche about fifteen years earlier, was doing well, but they subsidized their Dharma work by publishing a non-Buddhist list; only about twenty percent of their titles were Dharma books. Also, they had gotten very lucky early by having the huge distributor Random House take them on, which ensured their books coming to the attention of many, many bookstores, and by publishing a mega-bestseller, The Tassajara Bread Book. All that notwithstanding, much credit must go to Shambhala’s brilliant founder and publisher, Sam Bercholz.

Snow Lion had started in 1980 publishing books by the prolific translator and author, Glenn Mullin, and specialized in books on Tibetan Buddhism, politics and culture. Actually, in early 1984 the company was in dire straits and the possibility of Wisdom buying them out arose, but then Jeff Cox came on board, Snow Lion published His Holiness’s Kindness, Clarity and Insight just in time for his extensive 1984 American tour, and the rest is history. Amongst other things, the keys to Snow Lion’s success have been their wonderful list, ability to maintain low overheads and excellent quarterly newsletter/catalog.

The rise of Tibetan Buddhism in the West

Fuelling the development of these essentially Tibetan Buddhist publishers, however, was the exponential rise of worldwide interest in Tibetan Buddhism, which in 1989 would get an enormous boost when His Holiness the Dalai Lama won the Nobel Peace Prize and became a household name.

Why was it so popular? Of course, the overt expressions of support of celebrities like Richard Gere didn’t hurt, but it was much deeper than that. I think many of the things that appealed to me about the Dharma I heard at Kopan attracted other Western-educated people as well. Also, the failure of traditional religions, material wealth, mood-altering drugs, fame, power and politics to provide any lasting satisfaction over the past few decades sent many Westerners on a search for meaning in their lives, which ended when they encountered the teachings of the Buddha.

Buddhism’s ability to withstand analytical scrutiny, its scientific nature, the clear structure of the Buddhist path and, perhaps most of all, the living example of realized masters, who clearly did practice what they preached and had attained results that others wanted, all contributed to its great acceptance by normally skeptical Westerners.

Lama Yeshe passes away

In the early hours of the morning of the first day of the Tibetan New Year—the third of March, 1984—soon after we’d moved into the house in Streatham, we received a phone call from California that our beloved Lama Yeshe had died. Lama had been manifesting ill health for some time, and from the day I met him, I knew he had heart trouble, but the reality was still a shock. Robina and I flew to the United States for Lama’s cremation at Vajrapani Institute, his first American center, and returned to London to put together a commemorative issue of the new FPMT magazine, of which only one issue had been published so far.

Lama had often spoken of having a magazine to serve as the communicative glue between his many far-flung centers, to promote, as he put it, a “family feeling” among his international students. In 1983, therefore, we published the first issue of the new FPMT magazine, calling it Wisdom. Sadly, the second issue, the tribute to Lama Yeshe, would be the last, but about ten years later, it would reincarnate as Mandala, again with Robina as its editor.

Buddhist magazines

One of the first general-circulation Tibetan Buddhist magazines in the West was the Shambhala Sun, founded by Trungpa Rinpoche, whose students had also started Shambhala Publications. It began in newspaper format in 1978 as the Vajradhatu Sun, changed its name in 1992 and went into proper magazine format in 1993. Under the editorship of Melvin McLeod, its circulation climbed from just under 2,000 in 1991 to about 60,000 today. Coming out every two months, it is the most widely read Buddhist magazine of all.

Tricycle, which started in 1991 and has grown rapidly, is not a Tibetan Buddhist magazine, but often features teachings from Tibetan Buddhism and interviews with Tibetan Buddhist teachers. Published quarterly, it is not aligned with any particular Buddhist tradition, although its founding editor, Helen Tworkov, is a Zen practitioner. It is beautifully produced and its circulation is roughly the same as that of the Sun.

The Lama Yeshe memorial issue of Wisdom was a wonderful effort and a tribute to the skill and dedication of Robina, but with Wisdom Publications getting busier with books and mail order distribution, we just couldn’t keep it going.

After Lama Yeshe’s passing, Lama Zopa Rinpoche took over as spiritual director of the FPMT, and the organization continued to blossom, coming to benefit tens of thousands of people all over the world. With this growth, the need for some communicative glue became ever more pressing, and eventually Robina, who had left Wisdom in 1987, was asked to start another FPMT magazine. As noted, it was called Mandala, and became a great success within the FPMT, fulfilling Lama Yeshe’s original vision of something that would create a feeling of oneness and cohesion throughout his widespread organization. At first it was published every other month, but when Nancy Patton took over from Robina as editor at the beginning of 2001, it went quarterly. With a circulation of 5,500 when Nancy took over, it has grown to 12,000 in just over a year and Mandala is now becoming a great success even beyond the FPMT.

Wisdom moves to America

In talking about magazines, I jumped ahead in my story, where I was talking about Lama Yeshe’s passing. After that, in the mid-1980s, I took stock of Wisdom’s situation. When I compared Wisdom to Shambhala and Snow Lion, one obvious difference was that we were a non-profit, charitable organization and they were privately owned, but what appeared to be more significant was geographic—they were in America and we weren’t. The US market was the biggest in the world, especially for Dharma books, and we couldn’t access it properly from England.

Accordingly, with a little help from our friends, in 1987 we established our own distribution office in Newburyport, just north of Boston. A British businessman, who owned a large office building there, offered us free space, his marketing expertise and $50,000 a year for five years, provided we incorporated Wisdom in America and had a functioning board of directors. I readily agreed and later that year we transferred all our American business to Newburyport. With the expectation of a donation of $1,000 a week and greatly increased sales, that year we published more books than we ever had before, seventeen, running up quite a big bill with our Singapore printer.

Unfortunately, the dream didn’t last too long, as within months our friend’s business encountered many obstacles and he finished up having neither time nor money to give us and gradually needing even the space we were using. Thus, all the income from American sales was required locally and we stopped receiving funds in London. I was still finding it hard to get donations and had to borrow large amounts of money just to keep going.

Despite all these difficulties, we kept on publishing beautiful books to growing acclaim, if not income. A couple of our books won prestigious prizes, such as the Thomas Cook Award for the best travel book of the year (Stephen Batchelor’s Tibet Guide) and the inaugural Christmas Humphries Award established by the Buddhist Society (Ayya Khema’s Being Nobody, Going Nowhere). We also started publishing the most beautiful calendar in the world, the Tibetan Art Calendar, and initiated some major projects, including Deities of Tibetan Buddhism (which took fifteen years to accomplish!), Liberation in the Palm of Your Hand, The Nyingma School of Tibetan Buddhism and the wonderful “Teachings of the Buddha” series, including, eventually, the Long, Middle Length and Connected Discourses of the Buddha.

As Wisdom’s financial situation became increasingly dismal, in 1988 the Wisdom board asked Lama Zopa Rinpoche what he thought about our transferring the whole company to the American office. Rinpoche checked and agreed that that would be best, and asked Boston-based Tim McNeill, whom I’d invited into the board when we set up in 1987, to take over from me as director. The plan was also for me to come over to assist in the transition and become editorial director.

Thus, in May 1989, Wisdom moved from London to Boston, and my life underwent another great change. For the first time since I’d gotten involved in Dharma I wasn’t running the operation in which I was working, and for the first time in almost twenty years, I was receiving a salary. In London, although the others (and at the time we left there were twelve people employed, some of whom stayed on to develop Wisdom Books) were paid—admittedly low wages—I was merely supported, which was how I preferred it. I also preferred being in charge and having greater control over my life. Now I was becoming an employee.

Compared to the halcyon days of 1974, my life had somehow become very ordinary. I’d already lost my ordination in 1986 when, as Lama had predicted, London got the better of me and, with Lama Zopa Rinpoche’s reluctant permission, I disrobed. Although we were doing wonderful Dharma work, it was still up in the morning, go to the office, return home at night, like any regular worker. Of course, had my mind been stronger, I would have managed, but unfortunately, it was not. When I became a monk, I envisaged leading a life of study, meditation and teaching—I wanted to be just like my Lamas and help people in the way they did. Clearly, that was not to be.

So, I accepted my fate and looked on the bright side. I had never really wanted to run a business, which is what Wisdom was, and had always been interested in working directly on the teachings in order to make them available to others. This was my chance to get back to doing what I really wanted.

Unfortunately, even with relocation and new management, Wisdom’s financial position did not improve much, as the debt inherited from London was too great. Finally, in 1991, we wrote to the many kind people who’d lent us money over the years to see if they would convert their loans into donations. Thankfully, most did, which took an incredible load off our shoulders. It’s amazing how kind people can be. After that, my job changed from editorial director to director of development, which is American for fundraiser. Over the next four years, again due to kindness of many people, I managed to raise about $1 million, which really kept the company afloat and enabled us to push ahead with our mission of spreading the Dharma for the sake of all sentient beings.

A new Dharma publishing venture

Everything was going reasonably well except for one thing—we were not publishing many of our founders’ teachings. In the twenty years of Wisdom’s existence, we had managed to publish only six books by Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

In 1996, Lama Zopa Rinpoche suggested that we remove the archive of his own and Lama Yeshe’s teachings from Wisdom and established the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive, to focus more attention on this essential work. It was not that Rinpoche ever thought it important to make his own teachings available; he was thinking more of those of Lama Yeshe. Still, Rinpoche’s devoted students wished equally to preserve his precious speech in this way as well. He asked me and my wife, Wendy Cook—who was also working at Wisdom, running the marketing and publicity departments—to establish the Archive as an independent FPMT entity.

That was six years ago, and that’s what I’m still doing. As usual, no funds came with my new assignment, so once more, raising funds became the first priority. We decided that the best way to create awareness of the Archive and the treasures it contained was to publish free books of teachings, and we hoped that these books would inspire people to support us. Sponsoring the publication of free books is a well-established practice in the East, but relatively rare in the West. So far we have been quite successful, having published about fourteen books for free distribution, and we hope that other people will follow our lead. We’ve also prepared one book for publication by Wisdom, Lama Zopa Rinpoche’s Ultimate Healing, and several more are on the way.

The future

It is wonderful how interest in Buddhism has grown over the past three decades; wonderful to see how many Dharma books are being published and sold; astonishing to see a book by His Holiness the Dalai Lama spend more than a year on the New York Times bestseller list and find his books in airport bookstores all over the world. This development of Buddhism does not appear to be slowing down.

At first glance, a Buddhist looking at all this might feel optimistic, but not so fast. History shows that Buddhism has surged before, only to decline, and while the next few years look good, what we see today won’t last.

Although personally I believe that only Buddhism, purely practiced, can offer true peace and happiness to the world, it’s not going to happen. The world is getting worse, not better. Society is far too deluded and immature for Buddhism to gain wide acceptance. The planet is grossly overpopulated, and there are too few resources and far too many powerful and dangerous weapons in the hands of ignorant, angry people. The main problem, of course, is that we believe that happiness comes from external phenomena; we don’t understand karma, and how peace, happiness and satisfaction are created by the mind.

All we can do as individuals is to control our own minds, avoid negative actions and practice virtue to the best of our ability. The opportunities we have today might be the best we’ll have for a long time, and we should take full advantage of them while they last.

Books got me into this at the beginning, they’ve kept me going, and I hope they’ll be there at the end. I would like to continue editing and publishing Dharma books for the benefit of all sentient beings until the day I die. It sure beats being a boxer’s second.

References

Note: Snow Lion Publications was acquired by Shambhala Publications in May 2012. Snow Lion books listed below are now available from Shambhala.

Batchelor, Stephen. The Tibet Guide. London: Wisdom Publications, 1987.

Brown, Edward Espe. The Tassajara Bread Book. Boston: Shambhala Publications, 1970.

Dipamkara Shrijnana. Atisha’s Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment. Commentary by Geshe Sonam Rinchen; translated and edited by Ruth Sonam. Ithaca: Snow Lion Publications, 1997.

—.Illuminating the Path. Commentary on Atisha’s Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment by His Holiness the Dalai Lama. Translated by Geshe Thupten Jinpa and edited by Rebecca McClen Novick and Nicholas Ribush. Long Beach: Thubten Dhargyey Ling Publications, 2002.

Dudjom Rinpoche. The Nyingma School of Tibetan Buddhism. Translated by Gyurme Dorje and Matthew Kapstein. Boston: Wisdom Publications, 1991.

Gyatso, Tenzin, His Holiness the Dalai Lama. Kindness, Clarity and Insight. Ithaca: Snow Lion Publications, 1984.

Hopkins, Jeffrey. Meditation on Emptiness. London: Wisdom Publications, 1983.

Humphreys, Christmas. Buddhism. London: Pelican, 1951.

Khema, Ayya. Being Nobody, Going Nowhere. London: Wisdom Publications, 1987.

Pabongka Rinpoche. Liberation in the Palm of Your Hand. Translated by Michael Richards. Boston: Wisdom Publications, 1991.

Rabten, Geshe, and Geshe Ngawang Dhargyey. Advice from a Spiritual Friend. Translated and edited by Brian Beresford. New Delhi: Publications for Wisdom Culture, 1977. (Boston: Wisdom Publications, 2001.)

Russell, Bertrand. Why I Am Not a Christian, and Other Essays. (Current edition) New York: Simon & Schuster, 1977.

Shakyamuni Buddha. The Long Discourses of the Buddha. Translated by Maurice Walshe. London: Wisdom Publications, 1987.

—. The Middle Length Discourses of the Buddha. Translated by Bhikkhu Nyanamoli and Bhikkhu Bodhi. Boston: Wisdom Publications, 1995.

—. The Connected Discourses of the Buddha. Translated by Bhikkhu Bodhi. Boston: Wisdom Publications, 2000.

Sparham, Gareth. The Tibetan Dhammapada. Translated by Gareth Sparham. New Delhi: Mahayana Publications, 1983. (London: Wisdom Publications, 1986.)

Willson, Martin and Martin Brauen. Deities of Tibetan Buddhism. Boston: Wisdom Publications, 2000.

Yeshe, Lama Thubten. Introduction to Tantra. Edited by Jonathan Landaw. London: Wisdom Publications, 1987.

—. The Tantric Path of Purification. Edited by Nicholas Ribush. Boston: Wisdom Publications, 1994.

Yeshe, Lama Thubten, and Lama Thubten Zopa Rinpoche. Wisdom-Energy. Edited by Jonathan Landaw and Alexander Berzin. Kathmandu: Publications for Wisdom Culture and Honolulu: Conch Press, 1976. (Boston: Wisdom Publications, 2000.)

— et al. Teachings at Tushita. Edited by Glenn Mullin and Nicholas Ribush. New Delhi: Mahayana Publications, 1981.

Zopa Rinpoche, Lama Thubten. The Wish-Fulfilling Golden Sun of the Mahayana Practice. Kathmandu: Kopan Monastery, 1972.

—. Ultimate Healing. Edited by Ailsa Cameron. Boston: Wisdom Publications, 2001.

Buddhist magazines

Lion's Roar (previously Shambhala Sun). 1660 Hollis Street, Suite 205, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada B3J 1V7.

Mandala. 1632 SE 11th Avenue, Portland, OR 97214-4702 USA.

Tricycle. Find contact details here.